The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track planetary extreme, or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😜

Main Topic: Rising Seas Displace Islanders- Case In Point Fiji

Dear Diary. It is a fact that seas are starting to rise due to climate change…thankfully slow enough as of 2025 that people can adjust and move to higher ground. That may not be the case as we approach the end of this century. The poor canaries in the coal mine are residents of low lying small Pacific islands inhabited mostly by Polynesians.

The Washington Post has written a good article on how Fiji is coping with the invasion by the sea, which I am presenting for our main topic today:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/08/08/fiji-climate-change-village-relocation

Faced with rising seas and falling aid, Fijian villages move uphill

Mariana Sarawaqa stands among mangroves she planted to help protect the shoreline in Vunisavisavi, Fiji, where rising sea levels are threatening homes and a sacred gravesite. (Photos by Carolyn Van Houten/The Washington Post)

As the effects of climate change are felt across the Pacific, Fiji has become an authority on the logistically and culturally fraught process of community relocation.

8/09/2025 at 5:00 a.m. EDT

MUANI, Fiji — For years, this coastal village has tried to overcome the effects of climate change. When rising seas began to lap at their doors, residents built a seawall. When flooding continued, they dug culverts and trucked in rock and sand.

But the ocean now spills over the seawall, fills the culverts, and erodes the rock and sand. And so, villagers have decided it’s time to move. To move Muani, wooden house by wooden house, a few hundred yards to the top of a densely forested hill.

“It will be tough,” rasped Alivereti Taito, the 92-year-old chief, between cigarettes and cups of kava, a brown, peppery drink that has a mild numbing effect. “But I am worried about the village.”

Now the question is whether Muani can afford to wait for the government’s help, or whether it will have to move on its own.

Homes near the coast in the village of Muani on Fiji’s Kadavu island.

Fishing is central to Muani, a community where residents buy the day’s catch straight from the boat.

Over the past decade, Fiji has become a laboratory for an issue that will soon affect millions of people around the globe: climate-driven relocation. It was among the first countries to move a community threatened by climate change when, in 2014, it shifted the sinking village of Vunidogoloa a mile uphill on Fiji’s second-largest island, Vanua Levu.

Fiji has since become an authority on the logistically and culturally fraught process, with more than 40 villages — including Muani — earmarked for potential relocation. What this nation of 950,000 doesn’t have, however, is the money to relocate them all.

Developing countries have long demanded assistance from the wealthier nations responsible for the vast majority of the carbon emissions driving climate change. That help began to materialize in 2023 with the creation of a “loss and damage” fund, to which President Joe Biden pledged $17.5 million.

That momentum is now threatened. President Donald Trump has disbanded the U.S. Agency for International Development, which gave Fiji$10 million in assistancelast year including funding for climate resilience studies. He has pulled the United States out of the Paris agreement on climate change, rescinded $4 billion in related pledges, and left the loss and damage fund. Biden administration promises of more than $600 million for Pacific island countries, including for a new regional climate fund, are in limbo.

The State Department “continues to carefully review all current and potential assistance programs for alignment with President Trump’s foreign policy agenda of making America safer, stronger, and more prosperous, including in the Pacific,” a spokesperson said by email.

“We remain fully committed to continued engagement with Pacific island countries to identify opportunities to promote our shared interest in fostering greater peace and prosperity in the region,” the spokesperson said.

But the funding gap has created a void some analysts say could be filled by China, which Trump calls the United States’ biggest rival. In May, Beijing hosted a summit for 11 Pacific island countries including Fiji, after which they pledged climate cooperation. China also promised 100 “small and beautiful” climate projects in the region, although it’s unclear if any will involve village relocation.

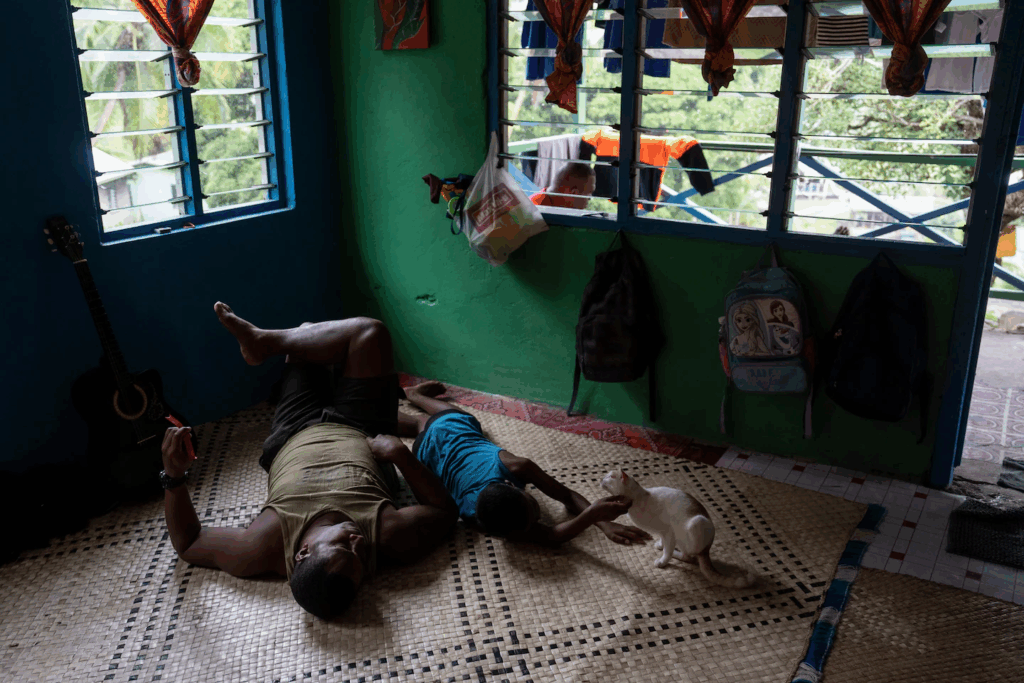

Lemeki Navusolo and Abraham Joji Seru, 10, rest at home in Muani.

Emile Tivitivi holds Luisa Bativucu, 2, in Cogea on Vanua Levu island in Fiji. Their home has previously flooded to the ceiling.

“The Chinese are seizing the low-hanging fruit that the Trump administration has offered them,” said Wesley Morgan, a climate and Pacific researcher at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

Fiji is trying to fund its own relocations, while also hoping that two villages in the process of being moved succeed and spur more international aid. But it doesn’t even have enough money to assess which villages should move.

The Fijian government did not respond to a request for comment.

Many villagers are tired of delays. Some communities have uprooted without government assistance.

Muani is heading in that direction. The village has allowed a state-owned company to harvest pine trees from its land, a decision that has led to soil erosion and made it harder to fish, but has also generated money that can be used for relocation.

Until the new site is cleared, however, villagers face a painful decision: whether to deepen their ties to a place that may soon cease to exist.

“I can’t wait for the village to move,” said Seru Tuicakau as he built a new house on extra-high stilts just 20 yards from Muani’s failing sea wall. The 38-year-old father of three had only three months at home before returning to Australia to pick oranges.

Sailosi Ramatu at the spot where his home used to be in Vunidogoloa, Fiji. The nation moved the village one mile uphill in 2014.

‘The ocean became our biggest enemy’

Waves lapped at Sailosi Ramatu’s knees as he stood where his house once was. A sea wall built decades earlier was hidden underwater. Another was in ruins on the beach. The 65-year-old raised a broken arm.

“My grandfather was born over there,” he said, pointing 10 yards out to sea. It had been a decade since Ramatu led the relocation of Vunidogoloa, the first village to be officially relocated because of climate change in Fiji — perhaps one of the first in the world. Its story shows the promise and perils now facing dozens of villages here.

“It was good living by the ocean,” Ramatu said. “But with climate change, the ocean became our biggest enemy.”

Pacific island nations are especially vulnerable. Sea levels in some parts of Fiji rose more than 11 inches between 1990 and 2020 — triple the global average — according to a 2024 United Nations report.

While attention has focused on sparsely populated, low-lying atoll nations such as Tuvalu and Kiribati becoming completely uninhabitable, 10 times as many people are imminently threatened in higher-sitting islands including Fiji, said Patrick Nunn, a geographer at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Australia.

About three-quarters of Tuvalu’s population — or 8,750 people — have applied for a visa to help people there escape the effects of climate change.

But for many in Fiji, the answer isn’t to move abroad but to move up.

Tents house people who were displaced by cyclones and are awaiting relocation in Nabavatu, Fiji.

Homes built by the U.S. Agency for International Development in Vunisavisavi.

For Vunidogoloa’s 140 or so residents, relocation began by leaving their home of more than 150 years. Like many Pacific peoples,Fijians have strongsocial and spiritual connections to the land, which theyconsidertheir ancestral and future home. Theyoften bury a child’s umbilical cordunder a hardy tree, spiritually tethering them to that place.

The move has been traumatizing for many in the community.

“We were born there, we stayed there, everything was there,” said chief Simione Botu. “When we came to the new site there was nothing.”

It took five years for the government to build about 30 houses, and even then they didn’t have kitchens — villagers had to add those themselves. People who had always fished had to learn how to farm or tend cattle. And for some elderly villagers, moving was “like taking them to a foreign land,” Ramatu said.

But there were improvements. Villagers no longer need rafts to leave home during storms or king tides. Getting to the hospital used to be difficult. Now, the village is on a main road. The houses have iron roofs instead of thatch. Most important, the villagers no longer live in fear of the waves.

Esala Tawake, in his tent home in Nabavatu.

Baseva “Ba” Diroko, in her home in Cogea.

Five other villages have since been relocated, completely or partially, with varying success. In Vunisavisavi, another coastal community not far from Vunidogoloa, a USAID plan to relocate the village of about a dozen houses was pared back to just four buildings in 2016. The new homes are sturdy and dry but are on a hillside with their backs to the village. Residents say they weren’t properly consulted.

“Before, it was a happy life,” said Lorima Bulimaitoga, 32. “Now we have sleepless nights, worried about landslides.”

Mariana Sarawaqa said villagers want the government to build a sea wall and raise the land — expensive and unlikely measures, especially so far from the capital, Suva, and tourism hub, Nadi. As they wait, an air of sadness has settled on Vunisavisavi. Some families have moved away. Sarawaqa has been teaching children to plant mangrove seedlings “to help the village not to drown.”

These missteps —building houses without kitchens, putting them on hillsides where people live in fear of landslides — led Fiji to overhaul its approach. In 2019, the government in Suva establisheda trust fund for village relocation partially financed by taxes on environmentally damaging goods and services, such as plastic bags and international flights. It also created a relocation task force and, in 2023, a 135-page standard operation procedure that is a model for other small island states.

But the trust has just $3.5 million, barely enough to move one village, said Leba Gaunavinaka, a specialist at Fiji’s Ministry of Climate Change. New Zealand is the only nation to chip in as other countries wait to see if Fiji can deliver on two current relocations.

Muani residents gather for a ceremony commemorating a community member who died.

People break for lunch during work to build new houses in Cogea.

In Nabavatu, patience is wearing thin. In late March, more than four years after tropical cyclones triggered a landslide, around 150 people were still living in tents.

There has finally been some progress, however. The government recently cleared a block of land and began preparations to build 37 houses for a total of $2.6 million. “We will be happy to get out of this jail,” Esala Tawake, 70, said.

Things have moved more quickly in Cogea, a village in the bend of a river a few hours away. Here, 18 houses were swept away four years ago. When the government was slow to relocate the community, Cogea turned to the Fiji Council of Social Services, a civil society organization funded by a German religious charity.

FCOSS was building two houses at an elevated site 10 minutes away, with another 28 planned for a total of $1.2 million. A dozen men from Cogea were busy hammering and sawing. Women from the community brought them food and gardened.

Many villagers still had “trauma” from the cyclones, said chief Paula Navosa. But the hammering in the distance gave him hope. “We are happy to be moving.”

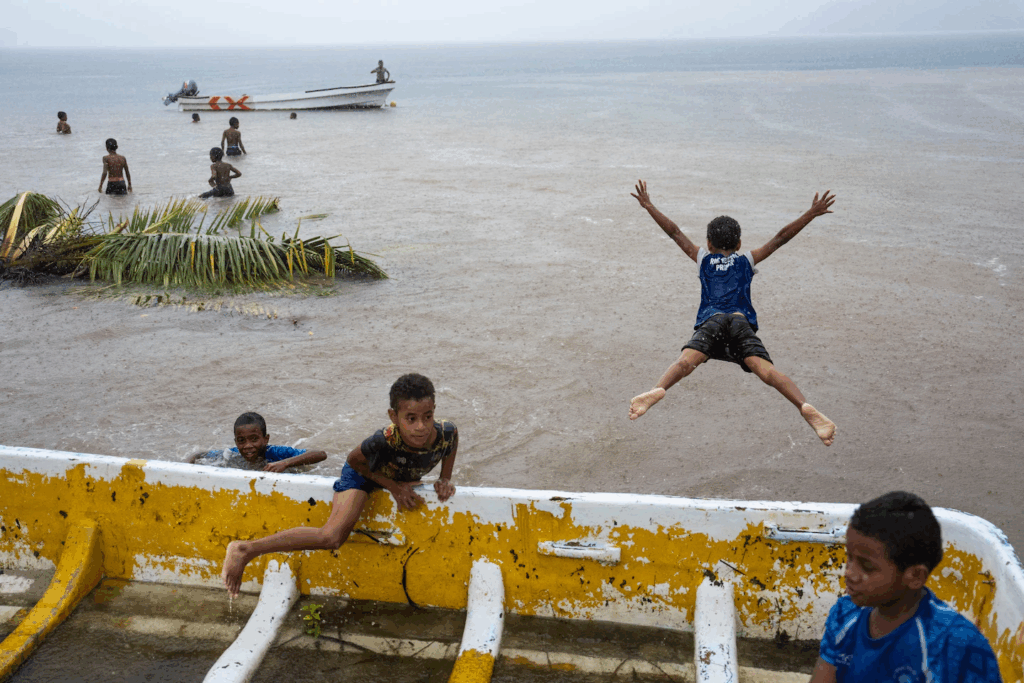

Children play in the Wainunu River, which has flooded the village and washed away several homes, in Cogea.

A village in climate limbo

On a Friday morning in Muani, four dozen students packed into an elementary classroom for a weekly quiz competition. “What is one effect of climate change,” asked headmaster Malakai Vucago.

“Rising sea levels,” replied a boy.

Even the youngest here understand the peril. Villagers have been discussing a move for a half-decade. In the past year, one of three local clans agreed to provide land on a hill above town. And in February, the community held a meeting with Fiji’s finance minister to ask for help clearing trees and connecting power and water.

Until that happens, however, villagers have no choice but to build at the old site, where the culverts and sea wall are increasingly ineffective.

The village teams’ rugby practice draws many residents as spectators, even in the rain. Some arrive in Muani by boat.

Children play in the rain near fishing boats in Muani.

Dan Area, Taito’s son who serves as acting chief, said the village was waiting on the government to approve the move and commit funds, but he feared that an election next year might upend things. In the meantime, logging was raising money that Muani eventually might need to relocate on its own.

Nunn, the geographer, said many villages are finding ways to move without government aid — something Pacific island countries will need to embrace as wealthy nations cut foreign climate aid either for ideological reasons or to address their own climate crises.

One way or another, Muani will have to move. When it does, not everyone will go. Malakai Kuve is one of several elders who vow to stay. As another high tide topped the sea wall, the 60-year-old recalled his childhood here with an old American pop song.

“Just a memory’s all that’s left of you,” he sang.

Malakai Kuve waits as his wife, Raikro Beitaki, watches the water level outside their home during a rainstorm in Muani.

By Michael E. Miller Michael E. Miller is The Washington Post’s Sydney bureau chief. He was previously on the local enterprise team. He joined The Washington Post in 2015 and has also reported for the newspaper from Afghanistan and Mexico. follow on X@MikeMillerDC

Here are more “ET’s” recorded from around the planet the last couple of days, their consequences, and some extreme temperature outlooks, as well as any extreme precipitation reports:

Here is More Climate News from Saturday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)