The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track global extreme or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😂

Main Topic: Expect Small Strains That Really Add Up from Climate Change

Dear Diary. There will be some unknown consequences from climate change moving forward through the 21st century that people have not thought of, most of which will be small results but will add up as negative factors against a sustainable civilization. These will become more apparent as the planet moves past +1.5°C above preindustrial conditions for average temperatures. It is incumbent upon all of us to insist to the powers that be that carbon pollution must stop as soon as possible to avoid known problems but lurking unknown catastrophes.

Alex Steffen written a brilliant essay discussing all this, which I am reposting for today’s main subject:

Things fall apart; the maintenance schedule cannot hold.

Things fall apart; the maintenance schedule cannot hold.

Climate foresight at a small scale.

Jan 29, 2026

The greatest pitfall in climate foresight is the assumption of continuity.

The assumption of continuity is the belief that the structure of past events — the fundamental linearity of baselines (in things like temperatures and growing seasons, snowpacks and sea levels), the former stability of systems around us, and historically experienced limits on the rate at which conditions can change — provides good evidence for evaluating what’s coming now.

The nature of discontinuity, though, is that what was true before becomes a poor guide for making decisions in the present.

Too rigid a clinging to continuity can even lead us to make choices with catastrophic outcomes, as our outdated thinking gets smashed by disruptive new realities. Assume Continuity and Find Out.

Indeed, the climate crisis is a crisis precisely because of the magnitude of discontinuity it’s driving into the systems, natural and human, upon which our civilization was built. That process is speeding up, meaning not only greater levels of discontinuity, but less time to prepare for tumultuous change.

We find ourselves in a moment of escalating discontinuity.

Why? The biggest reason is our failure to rebuild our economy for sustainability and decarbonization. We needed a sharp bending of the curve on climate emissions, ecological destruction and toxic pollution, and our opponents prevented us from getting it. The Last Decade has become the Lost Decade.

As an excellent recent piece in Yale Environment 360 puts it:

“The 1.5ºC target was set at the Paris climate conference a decade ago… [C]limate scientists say that 10 years of weak action since mean that nothing can now stop the target being breached. ‘Climate policy has failed. The 2015 landmark Paris agreement is dead,’ says atmospheric chemist Robert Watson,” former chair of the IPCC.”

That failure has transformed the human future.

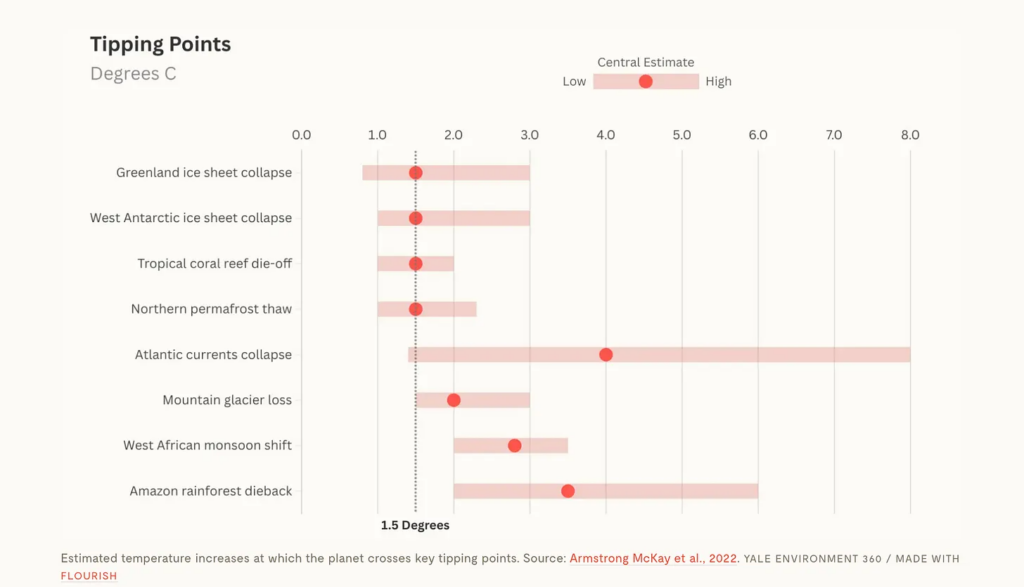

“Meanwhile, a picture of what lies ahead is becoming clearer. In particular, there is a growing fear that climate change in the future won’t, as it has until now, happen gradually. It will happen suddenly, as formerly stable planetary systems transgress tipping points — thresholds beyond which things cannot be put back together again.”

If we don’t radically alter course — and, let’s be real, there’s little sign that’s happening yet — we will, sooner or later, begin triggering planetary tipping points. Natural systems (upon which our very ability to manage our societies depends) will snap into new states, rendering every place, human system and pattern of living permanently altered. Even at 1.5ºC, we’re teetering on the threshold of a one-way visit to an alien world.

But we don’t even need to collapse the ice sheets and ocean currents or kill the Amazon to find ourselves hurtling into an undiscovered country of “what the frack is happening?”

Unprecedented disasters are each themselves discontinuities, and there’s abundant evidence that truly extreme weather is becoming more common. Hottest decade, year and month on record, heaviest rainfall in 24 hours, the costliest peacetime urban firestorm, the strongest hurricane wind gusts, deepest droughts — recent years have kept the hits coming.

Expect more. Last summer, NASA released data revealing a rapid intensification of extreme weather disasters. The article I link to there goes on to cite an unnamed “Met Office expert” warned that people are unprepared for such extreme events, “which would be outside previous experience.”

We fool ourselves, though, if we think that transapocalyptic tipping points and unprecedentedly heavy weather are the only ways we’ll feel the torque that transformed conditions put on unchanged societies. The small pressures may well, in aggregate, be the biggest and most disruptive.

This winter, maintenance has come back into fashion. A number of us seem, suddenly, to be remembering just how much effort it takes to rescue from entropy the infrastructure and supply chains that underpin our daily life. Keeping the world running was hard work, even when the world didn’t change that much from year to year. (As a side note, I’m looking forward to reading Stewart Brand’s new book Maintenance of Everything.)

“You live in a world of sand castles that are constantly falling apart,” Noah Smith wrote recently, “and only the constant maintenance effort of billions of people keeps it from turning into a post-apocalyptic movie in a matter of months.”

The single best way to understand what the climate crisis means to you is to think in terms of climate brittleness. But here’s a twist: If most folks don’t get how hard it is to keep the world running, even fewer understand that climate brittleness is essentially an increase in demanded maintenance and preparation.

Everything humans have made was made with a certain sense of normal in mind. Within a given range of tolerances, that thing will work more or less as expected, until it wears out.

Climate chaos nudges the context for every object and system in our world, pushing them into conditions that exceed their design tolerances. As tolerances are exceeded, wear and tear rises, deferred maintenance costs more, direct impacts cascade more easily and interconnections fail more frequently… unless you work harder. That need to work harder, in turn, undermines the capacities you previously had to do other things. Things fall apart; the maintenance schedule cannot hold.

We’re down to three choices: work harder, everywhere, just to keep what we have (and rebuild what we can when things break down); abandon the places and systems where it’s too hard to do that, to minimize our losses; rebuild what we have now, to ruggedize it for the conditions it will face in the future.

We’ll be doing all three, but we won’t keep up.

We are running a losing race with brittleness, in most places. We’ll hang on longer than we should in the most endangered places. We’ll start letting systems degrade. Ruggedizing our societies for conditions no one has ever experienced is already politically contentious, and we’ll find we don’t have the resources to do it everywhere, anyway.

We are trained to think of climate impacts as huge, monstrous things — giant dinosaur weather-beasts rampaging across our cities. But it turns out we should be at least as worried about the plague of small strains spreading through our lives, eating away at systems functionality like a horde of gnawing rodents. Cascading, interconnected, unpatterning and abrasive minor embrittlements.

The consequences of these small erosions will pile up around us. Even in the next decades, almost nothing we use will work quite as we expect it to, or cost what it once did, or be as easy to keep running as it once was. And we’ll be hassling with those realities when the bigger storms slam through, when the drought stretches on, when the wildfire crests the hilltops.

None of this is evenly (much less fairly1) distributed. The risks of huge disasters differ from place to place, but so to does exposure to brittleness. Even in a world tumbling over planetary thresholds, some places and systems will do better than others. Some ruggedization efforts will work better than others. Some communities will have more wealth and capacity to adapt than others. Some people will plan for discontinuity more sensibly than others.

Not everyone will even experience these impacts as losses — some places and groups will find opportunities they never had before, perhaps even successes at scales that would surprise most people today. (Though economic disruption and the geographic redistribution of wealth means further instability.)

No one, though, will find their way back to “how things have always been.”

The unprecedented is the only future we get.

Here are some “ETs” recorded from around the planet the last couple of days, their consequences, and some extreme temperature outlooks, as well as any extreme precipitation reports:

Here is More Climate News from Friday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)