The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track global extreme or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😉

Main Topic: More on a Climate Changed Polar Vortex Affecting Extreme Cold

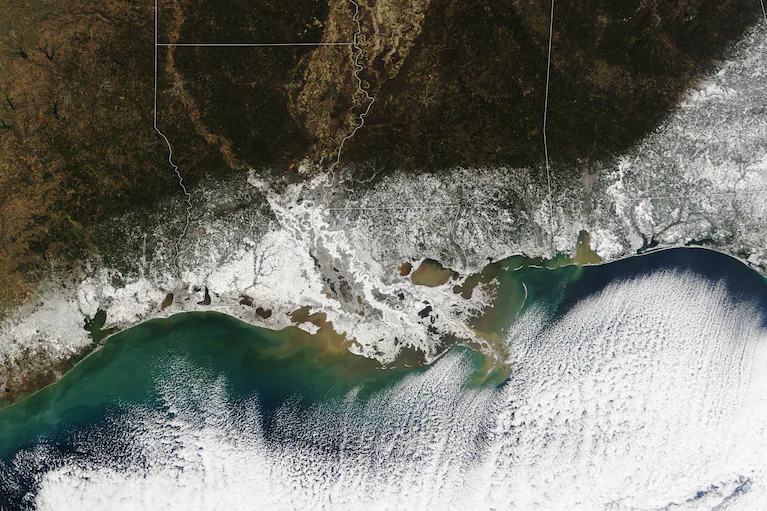

Dear Diary. It now appears that the planet just had its warmest January in recorded history despite the U.S. having a below average first month of the year, all thanks to climate change. A frigid Arctic blast that I dubbed chilled much of the Midwest during the middle of this month and was responsible for aiding to historic snowstorm for Gulf Coastal states:

So, how can Arctic blasts of epic proportion affect portions of the Northern Hemisphere in winter during this age of increased global warming? Again and again, I will point to the work of Dr. Jennifer Francis who has pointed out that occasionally we will have a stratospheric warming event drawing up from the south vast quantities of warm air at the jet stream level, which in turn forces pools of cold air to the south in the form of an Arctic blast.

Granted, this process has produced traditional cold outbreaks in the past when the climate was cooler, but the amount of potential warm air that can be injected northward from lower latitudes to interact with the polar vortex has greatly increased. I suspect that we will continue to see historic Arctic outbreaks until the polar vortex weakens so much that cold pockets can’t be forced south because these won’t exist. Hopefully that date will be never the first if we can just get our carbon polluting house in order.

Here are more details in a great new summary from the Washington Post:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2025/01/30/polar-vortex-disruptions-warming-extreme-cold

Warmth is weakening the polar vortex. Here’s what it means for extreme cold.

Research has found that rising temperatures in the Arctic are weakening weather systems that normally trap the cold around the poles, making winter weather more chaotic.

January 30, 2025

A storm this month brought below-freezing temperatures and heavy snow to the southeastern United States. (Wanmei Liang/MODIS/NASA)

By Scott Dance

The blast of cold that fueled record snowfall across Gulf Coast beaches last week was just the latest to transport frigid air that normally swirls above the North Pole to places much farther south — a phenomenon that researchers connect to a warming climate.

While scientists say that there is not evidence that extreme cold is becoming more frequent or intense, a growing body of research is finding that rising temperatures in the Arctic are weakening weather systems that normally trap the cold around the poles, making winter weather more chaotic. This shift is encouraging the erratic weather patterns high in the atmosphere that can cast chills even on regions with typically balmy climates, some research suggests, threatening to overwhelm communities not prepared for such frigid conditions.

Last week’s intrusion of polar air followed events like one that overwhelmed Texas’s power grid in 2021 and another that set record lows across the hardy Midwest in 2014.

It remains to be seen if that means unusually frigid outbreaks of winter cold will become more common in places like the United States and Europe, scientists caution.

The idea linking extreme winter cold with human-caused Arctic warming was considered radical a dozen years ago, when Jennifer Francis first led a study on it. Research has since strengthened that connection, she added — though it hasn’t answered all of scientists’ questions.

“The more we dive into it, the more complicated the story gets,” said Francis, a senior scientist at Woodwell Climate Research Center.

How Arctic air plunges southward

After all, the surging greenhouse effect as humans burn more fossil fuels is triggering three times as many observations of record high temperatures than record lows. Each of the past two years were significantly hotter, on average, than any other period in human history.

The poles will always be the coldest spots on the planet. That’s because for half the year, Earth’s tilted axis means they receive little to no sunlight.

Even through the summer, they have historically remained ice-covered — though that has dramatically diminished in recent decades. Arctic ice has seen what scientists found to be “irreversible” thinning since 2007; Antarctic sea ice hit a record low, by far, in 2023.

During many memorable episodes over the past decade or so, the cold air has shifted far from where it normally swirls.

Cold outbreaks —including an episode in January 2014 that brought the coldest winter in the Midwest in decades — introduced much of the public to the polar vortex. The phrase refers to a naturally occurring column of rapidly circulating air over the poles in the stratosphere, from 10 to 50 miles above Earth’s surface. That air swirls well above the troposphere, which is the layer closest to the ground, where weather happens.

The vortex can sometimes shift away from the pole, stretch or even split in a way that sends bitter cold plunging into midlatitudes.

Those disruptions to the circulation are happening more often as global warming has weakened the polar vortex. What’s less clear is whether those events are also leading to bouts of cold on the ground.

A strong polar vortex — and one that stays swirling tightly above the pole — depends on a dramatic contrast between frigid polar temperatures and milder conditions across midlatitudes. As rapid Arctic warming decreases that contrast, the vortex often isn’t spinning as tightly and is more prone to send its cold air spilling away from the pole.

“You need really cold air in the pole to have a very fast-spinning polar vortex,” said Mostafa Hamouda, a postdoctoral researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Any warming “slows the whole circulation down.”

That warming and slowing can allow the polar vortex to become increasingly stretched out — oblong, instead of tightly circular — and can spread its chill into latitudes with typically balmy climates.

Sometimes, lobes of the polar vortex can separate and get stuck well to the south. Multiple studies have strengthened scientists’ understanding of the phenomena as a consequence of Arctic warming and climate change.

Even if these disruptions in the vortex are not causing cold outbreaks to become more frequent or intense in the United States or other parts of the world, they may be translating into outbreaks of cold weather that are more widespread and last longer, Francis said. Her research suggests Arctic cold is also extending farther south into areas that are not well prepared for such conditions.

Newer studies also back up the idea that warming of the Arctic and the oceans may be encouraging weather patterns that allow polar air to spill southward for longer, more stubborn stretches of cold.

Those patterns — called blocking patterns — have always developed from time to time. They occur when areas of high pressure get in the way of the jet stream, a river in the upper atmosphere that steers the weather. And, as their name suggests, they can allow certain weather patterns to remain stubbornly in place — including undulating jet-stream patterns that allow Arctic cold to flow south into the United States, for example.

One recent study by Hamouda suggested warmth in the North Pacific is causing those blocking patterns to form more often and encouraging bouts of cold weather across the eastern United States.

Other research is inconclusive.

A ‘more complicated’ connection

One 2023 study found “no detectable trend” in midlatitude cold extremes tied to Arctic warming, including across the eastern United States, northeast Asia and Europe. Another from 2020 found that analyses and observations “continue to obfuscate a clear understanding” of how Arctic warming may be affecting weather at lower latitudes.

NASA scientists from the ICESCAPE mission study how changing conditions in the Arctic affect the ocean’s chemistry and ecosystems. (Kathryn Hansen/NASA)

Simple physics suggests changes to polar vortex and jet-stream patterns are logical responses to the dramatic changes humans have caused to Earth’s natural systems, said Andrew Dessler, director of the Texas Center for Climate Studies at Texas A&M University. “I don’t think there’s a lot of disagreement there,” he said.

The question is whether those larger atmospheric changes are translating into significantly colder temperatures on the ground, he said.

“I think that is the missing link,” Dessler said, adding, “Lots of things happen in the stratosphere that don’t make it down to the surface.”

Francis agreed the connection between global warming and cold-weather outbreaks is “much more complicated” than the well-established links to heat waves, droughts, sea-level rise, extreme precipitation and intensifying storms.

Still, she added, “the evidence supporting the link is more solid now.”

Some, like Dessler, will remain skeptical until research establishes a clearer link. But that does not diminish the dramatic changes happening to weather and climate systems or rule anything out.

“Nothing is the same in the climate as it was,” he said.

By Scott Dance Scott Dance is a reporter for The Washington Post covering extreme weather news and the intersections between weather, climate, society and the environment. He joined The Post in 2022 after more than a decade at the Baltimore Sun. Follow on Xssdance

Here are more “ETs” recorded from around the planet the last couple of days, their consequences, and some extreme temperature outlooks, as well as any extreme precipitation reports:

Here is More Climate News from Friday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)