The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track planetary extreme, or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😜

Main Topic: Thousands March for Climate Action as COP30 Talks Enter Second Week

Dear Diary. Yesterday we delved into insidious fossil fuel interests corrupting recent COP meetings. Today I’m emphasizing that there are still thousands of people around the world willing to drop their daily routines, organize and then march to protect our climate, pointing to what COP representatives should do.

Remember what Greta Thunberg and kids following her did during the late 2010s before covid put an end to their marches? After the early 2020s marches for our climate are back, only this time from adults. Here are more details from the New York Times:

Thousands March for Climate Action as COP30 Talks Enter Second Week – The New York Times

Thousands March for Climate Action as U.N. Talks Enter Second Week

As the talks continue, some countries are pushing for a detailed “road map” for a global transition away from oil, gas and coal.

A demonstration near the U.N. climate summit in Belém, Brazil, on Saturday. The atmosphere has been a marked contrast to the past three summits that were held in countries where governments restricted public protests.Credit…Andre Penner/Associated Press

By Lisa Friedman Brad Plumer and Max Bearak

Reporting from Belém, Brazil

Nov. 17, 2025, 5:02 a.m. ET

Thousands of climate activists flooded the Brazilian city of Belém this weekend, marching with a giant inflatable Earth, singing, dancing and demanding that nations gathered for a global climate summit at the edge of the Amazon rainforest take action to protect the planet.

But inside the negotiating halls where the United Nations conference, known as COP30, is entering its second week, the mood was less festive. Numerous issues remain unresolved as government officials confront the gap between the pledges they have made to reduce their greenhouse gases and the ambition required to stave off rising global temperatures.

“We know the world is off track,” said Manish Bapna, the president of the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group. “Now it’s all about how we get back on track and how we translate promises into real change on the ground,” he said.

Ten years ago in Paris, nearly 200 nations agreed to keep the average increase in global temperature to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), and preferably closer to 1.5 degrees, compared with preindustrial levels.

But emissions have increased significantly since then. Carbon dioxide from the burning of oil, gas and coal — the main driver of climate change — is on track to hit a record high this year. The world has already warmed about 1.3 degrees Celsius since the 19th century, and scientists have estimated that current policies will likely lead to around 2.8 degrees Celsius of warming by the end of the century.

In Belém, the world leaders who made lofty speeches about climate action during the first week are long gone. The diplomats who remain in the makeshift corridors of COP30, constructed atop an old airfield, have shed their jackets as the air-conditioning systems struggle and fail in the tropical heat. Water drips through the roofs during ferocious afternoon downpours as attendees hash out what more they can do to make progress in tackling climate change.

“Every one of your populations and economies need us to get results here in Belém,” Simon Stiell, the U.N. climate chief, told attendees on Saturday.

In the coming days, ministers are expected to arrive to narrow down sticking points and try to agree on concrete actions. The United States, which under the Trump administration is walking away from global climate commitments, is not part of the discussion.

The absence of the United States, the world’s largest historical emitter, has left the gathering without its most influential voice. Some argue that it has made things easier.

Among the topics of debate: How to make more funding available for developing nations so that they can protect themselves against the effects of climate change and how to handle trade barriers on clean energy technologies.

Small island nations, which are disproportionately vulnerable to rising sea levels and other climate-fueled disasters, are also pushing for COP30 to formally address the weakness of nations’ targets and hold countries accountable for not doing more.

Some officials, fearing that the talks could end up delivering a thin response on climate, are urging their colleagues to confront even more contentious issues.

Demonstrators in Belém on Saturday. Carbon dioxide from the burning of oil, gas and coal is the main driver of climate change. Credit…Andre Penner/Associated Press

Foremost among them is whether countries will build on an ambitious but vague promise made two years ago at a summit in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, to begin “transitioning away” from oil, gas and coal.

A group of countries — including Britain, Colombia, Denmark, France, Germany, and Kenya — are proposing that the summit create a detailed “road map” for how that transition might happen. It could, for instance, suggest that governments reduce subsidies for drilling and gasoline consumption.

“The Marshall Islands has been vocal in the rooms on the need for a fossil fuel road map,” said Bremity Lakjohn, the environmental minister of the Marshall Islands, which is at high risk from rising sea levels. “We will keep raising our voices as our island nation is sinking.”

But any effort to get more specific about phasing out fossil fuels is almost certain to face opposition from major oil and gas producing countries at the summit, including Saudi Arabia and Russia.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil had suggested the fossil fuel road map in a speech at the beginning of the summit, although his country is a case study in how difficult that transition can be. Brazil recently granted a license to its state oil company to explore for new sources of oil near the mouth of the Amazon River.

And the United States, while not participating in the talks, is moving quickly under the Trump administration to produce more fossil fuels. It is also pressuring other nations to buy them.

The Brazilian diplomat in charge of the negotiations, André Corrêa do Lago, has said that he would prefer to avoid the kind of last-minute fights among countries that have come to define these annual climate talks. In the past, negotiators have bickered in all-night sessions over whether nations should promise to “phase out” or merely “phase down” coal, or quibbled about the precise wording on a document intended to signal to the world that governments were serious about weaning themselves off fossil fuels.

Mr. Corrêa do Lago said he wanted the summit to focus on realizing past promises on aid for adaptation and shifting to cleaner forms of energy rather than trying to make splashy new commitments.

“This obsession with having new decisions is something that maybe we have to compare with what we already have,” Mr. Corrêa do Lago said last week.

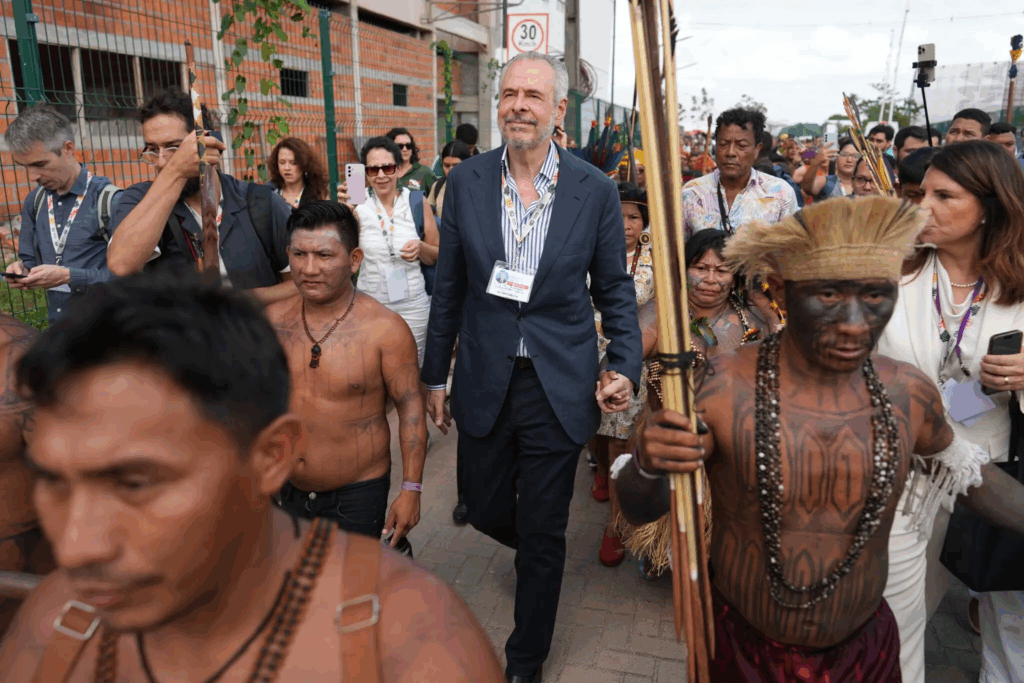

André Corrêa do Lago, the Brazilian diplomat shepherding the climate talks, walked with a group Indigenous protesters near the conference venue on Friday and intervened when they blocked an entrance. Credit…Andre Penner/Associated Press

For all of the doubts about the efficacy of the U.N. climate summits, many here have said that the Brazilian team leading the negotiations has been fairly inclusive.

That energy has been on display in public, too. On Friday, when Indigenous protesters blocked the entrance to the conference venue, Mr. Corrêa do Lago personally intervened. Their conversation, which lasted nearly an hour, was calm.

At one point, a protester foisted a young child into Mr. Corrêa do Lago’s arms, and he beamed with a smile. The protesters disbanded shortly after, allowing the event hall to reopen.

The atmosphere in Brazil, a democratic country, has been a marked contrast to the past three summits in Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Azerbaijan — autocratic states where the government often severely restricts public protests. This year’s gathering boasts a boisterous and influential array of people’s movements, trade unions and activist organizations.

Protests have not just been allowed here, but encouraged. Saturday’s march through the heart of Belém was on a route approved by the local police.

10 Years After a Breakthrough Climate Pact, Here’s Where We Are

Lisa Friedman is a Times reporter who writes about how governments are addressing climate change and the effects of those policies on communities.

Brad Plumer is a Times reporter who covers technology and policy efforts to address global warming.

Max Bearak is a Times reporter who writes about global energy and climate policies and new approaches to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Here are some “ET’s” recorded from around the planet the last couple of days, their consequences, and some extreme temperature outlooks, as well as any extreme precipitation reports

Here is More Climate News from Monday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)