The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track planetary extreme, or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😜

Main Topic: Fixing Forests or Fueling Fires? Scientists Split Over Active Management

Dear Diary. As the climate crisis deepens the world’s forests will become more stressed. Beyond drought and increased heat leading to more wildfires, infestations from insects such as pine beetles will kill more trees. Without forests the planet doesn’t have much ability to regulate atmospheric oxygen supplies, and carbon dioxide doesn’t get absorbed to keep Earth cool enough for most life.

The following Mongabay article gives details about a debate among scientists who want to deal with the planet’s forests. Increasingly I seriously doubt that substantial intervention will be done due to high costs and what we as a society have done in association with the climate crisis:

Fixing forests or fueling fires? Scientists split over active management

Fixing forests or fueling fires? Scientists split over active management

13 Aug 2025

- After years of questionable policies, climate change and growing populations, wildfires have gotten worse in the western U.S., and around the world. That’s driven a push to use tools like thinning and controlled burns to reduce risk and restore natural fire patterns.

- Many researchers argue that the damage inflicted means we need to apply these “active management” tools thoughtfully and tailored to each forest’s conditions.

- But some scientists warn that too much intervention can harm ecosystems, especially old-growth forests.

- The debate has led to scientific and legal battles, ultimately centering on questions about the role people can play in helping forests recover in the face of increasing fire risk.

This is the first installment of Mongabay’s coverage of active management tools for forest fires.

On Sept. 8, 2020, a brush field in southern Oregon, in the northwestern U.S., caught fire. Over the next week, “walls” of flame tore through the towns of Talent and Phoenix in the Rogue River Valley. Here, hot, dry summers crisp low-lying vegetation, and convective winds — like those that kicked up in early September 2020 — can fan the spread of fire from even the smallest ignition.

The 1,300-hectare (3,300-acre) Almeda Drive Fire was small by contemporary standards in the U.S. West, where blazes repeatedly shatter records. And this one was human-caused, as are more than 80% of fires in the U.S. But neither statistic made it any less devastating to the families of Talent and Phoenix, more than 2,600 of whom lost their homes to the blaze.

Amid a swirling mix of past mismanagement of forests in the western U.S., an explosion of dense settlements, and hotter, drier conditions on account of climate change, there’s been a push in recent decades to actively manage forests for fire risk — aimed at avoiding disasters like the Almeda fire. The idea is that management tools such as forest thinning, prescribed burning and post-fire restoration can help claw back some of the characteristics of how forests used to be, when fire itself was a more active part of the landscape. The scientific literature is stacked with studies on the nuances of “active management,” both how to tailor it to different forest ecosystems, and arguing evidence for its success.

Active management is even the basis for the Fix Our Forests Act, a rare piece of legislation in the U.S. with support from both major political parties. Democrats and Republicans seldom see eye to eye these days, but both parties have come together to craft and support the bill, in the hopes of assuaging their constituents’ fears for their homes, insurance premiums, recreation areas and lives.

But Dominick DellaSala, formerly chief scientist of the Wild Heritage Project at the Earth Island Institute, a California-based nonprofit, says the push for sweeping active management in forests isn’t just wrongheaded — it could be dangerously destructive and may not reduce the risks of fire.

Photographs show how the density of trees at California’s Emerald Bay State Park has increased between 1883 and 2018. Image © California State Parks.

“They’re spending tens of millions of dollars in my watershed here doing logging and burning, and it didn’t help at all,” says DellaSala, who lives in Talent, Oregon, near where the 2020 Almeda Drive Fire started. “This is very emotional for me.”

DellaSala, now with the Oregon-based Conservation Biology Institute, and his colleagues say the Fix Our Forests Act could decimate forests if implemented, pointing, as well, to a March 2025 executive order from President Donald Trump to vastly increase logging on federal land.

Arguments over fire risk management have simmered for years, with a group of scientists, including DellaSala, bucking the broader consensus that more intensive active management is the only hope for saving these forests — and the homes and infrastructure adjacent to them. DellaSala is quick to point out that they don’t advocate “doing nothing.” In a recent paper published in the journal Biological Conservation, they call for a pared-down approach to active management, one that protects stands of old-growth forest where they remain, curbs the use of both heavy machinery and “recurrent” prescribed burns, and guards against commercial logging masked as thinning. He and his colleagues argue the misapplication of these tools can destabilize the ecological underpinnings of once-vibrant ecosystems, effectively sanitizing the canvas on which animals, plants and fungi can no longer flourish or even survive. And rather than mitigating risk, they say, this approach can also potentially set the stage for more frequent and more severe fires.

“What we’re doing is not the corrective course,” DellaSala says. “It’s only going to make things worse.” DellaSala and his like-minded colleagues say efforts should be focused on hardening homes and addressing the continuing release of carbon dioxide from human activities that’s causing climate change, rather than a larger focus on active management.

Researchers like Paul Hessburg, however, are pushing back. In more than four decades studying western North America’s forests, Hessburg has documented how fire suppression policies, intensive logging and the removal of Indigenous peoples — who themselves managed forests with tools including fire for millennia — have significantly altered the fundamental nature of some forests. Hessburg’s work, along with that of many forest researchers and fire ecologists, has convinced him that our incessant meddling with previously balanced ecosystems has left us little choice but to intervene.

“It’s absolutely necessary,” he says, adding that the critical questions should revolve around which tools to use in which circumstances — not whether active management is necessary. In 2021, Hessburg and 19 other researchers penned a point-by-point response in the journal Ecological Applications to the arguments commonly laid out by active management skeptics. They cited numerous studies to demonstrate the role active management tools can play in helping forests adapt.

Though he and DellaSala disagree on many things, Hessburg, too, advocates for a nuanced approach to active management. He calls for leaving long-lived, fire-adapted trees on the landscape during thinning operations aimed at removing younger trees that can intensify fires. He says management should be tailored to the unique dynamics of individual ecosystems, so that the same tools used in the dry mixed conifer forests of the Sierra Nevada aren’t employed in, say, the temperate rainforests of the Pacific Northwest.

But Hessburg also bristles at what he sees as reactionary opposition to all things active management by the DellaSala crowd. In some cases, conservation organizations have sued to stop government agencies like the National Park Service from doing active management in the name of protecting forests.

The past two centuries have vastly altered forests in the western U.S. A key question now is whether those changes mean we must now use some of the same tools to help them persist throughout the 21st century and beyond. Or is the approach of active management misguided, instead setting entire ecosystems up for collapse?

The Lick Creek Fire at Umatilla National Forest in Oregon in July 2021. Image by Brendan O’Reilly (U.S. Forest Service – Pacific Northwest Region) via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

‘Inevitable’ fire

Critical to the active management strategy is finding ways to replicate processes that occur naturally or originated from the Indigenous peoples who lived amid these forests for thousands of years. Proponents say it’s those very techniques that allow these forests to continue to provide habitat, carbon storage and other ecosystem services.

Fighting the risk of big fires in the climate change-dominated Anthropocene, however, requires grappling with the unavoidable return of fire, in some form, to the dry forests of the West.

“Everything comes down to the inevitable fire,” says Sean Parks, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service. “For me, it’s gonna burn.”

Indeed, fire has long been a part of many temperate, dry forests, adds Parks, who was a co-author, along with Hessburg, of the Ecological Applications paper responding to criticisms of active management.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that … basically, fire exclusion was the worst thing we could have done to our forests,” Parks says.

Two photographs show the increasing density of forests as a result of fire exclusion. Image courtesy of Paul Hessburg.

In fire’s absence, the biomass of fallen trees, branches and detritus — in a word, “fuel” — accumulates over decades, pushing the risk of severe fire to dangerous levels in forests, according to many scientists.

To Hessburg, it’s not about whether to do active management to benefit forest health, lower fire intensity and decrease the destructiveness. The science supporting active management is “very much settled,” he says.

“The question is, how would you use the tools to produce something that will invite fire actively back to the landscape?” Hessburg adds. “Because that’s essential, and that would adapt that landscape to climate change.”

In the dry coniferous forests of the U.S. West, appropriate active management might start with thinning the forest to get rid of crowds of younger trees, along with shrubs and other vegetation that have popped up in the absence of fire. Once they’re gone, land managers might start a cycle of prescribed burns. The idea is that with less woody material on the ground and fewer “ladder” fuels — branches on younger trees that shuttle the flames into tree crowns — these prescribed burns will replicate the work that lower-severity fire had been doing for ages. Active management also includes a set of tools after a fire burns to remove potential fuels from the ground, again to diminish fire intensity.

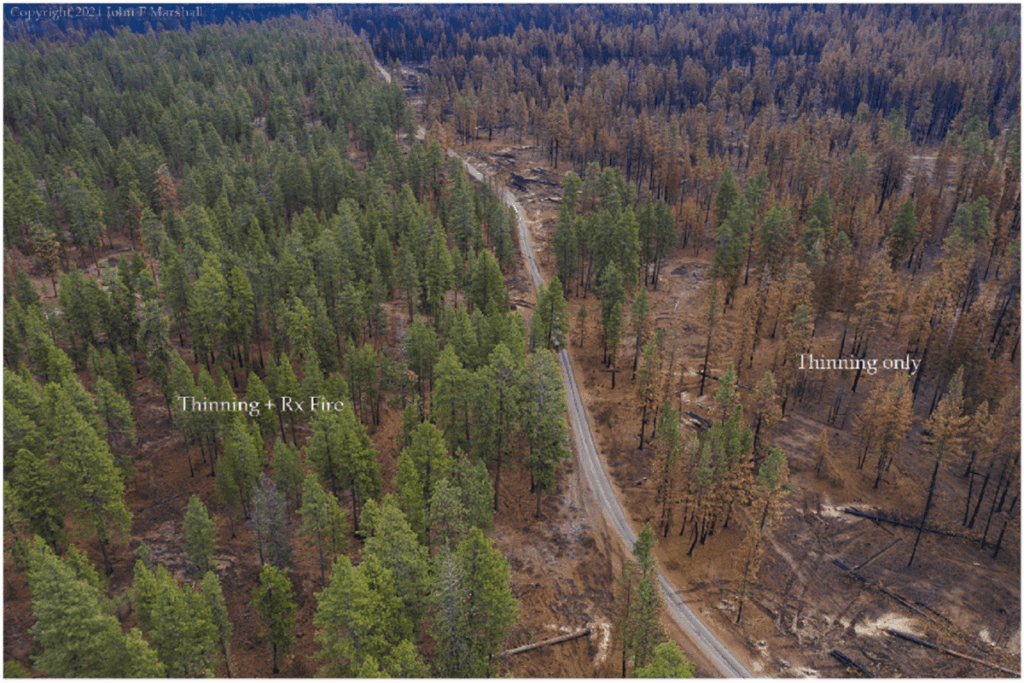

Proponents of active management argue that treating forests with both prescribed burning and thinning can reduce fires’ destructive potential compared to thinning alone. Image courtesy of Paul Hessburg.

Are the tools to blame?

But a primary contention of active management skeptics like DellaSala is that applying the same tools that caused the problems in the first place is illogical.

“That’s circular reasoning,” DellaSala says. “You can’t ignore the consequences, the collateral damages to ecosystems, the amount of emissions put into the atmosphere from logging to contain natural disturbances.”

He and his colleagues question the broad application of these tools. They say that thinning, for example, is often used as an excuse to take out larger, more valuable trees for commercial logging, when these trees should be left behind because of their importance in biodiversity and carbon storage. Old-growth trees not only anchor ecosystems, but are often the most resistant to climate-driven shocks like fire, drought and beetle infestations.

“When we do active management, we choose which trees die, which ones remain, and we probably have it mostly wrong,” says Diana Six, a forest entomologist and professor at the University of Montana who frequently collaborates with DellaSala. Removing resistant trees means that their genes won’t filter down to the next generation, she adds, potentially setting up even greater vulnerabilities later on.

“We’re not allowing those forests to adapt, and adaptation is what we really need,” Six says. “Everybody pushes resilience. Resilience is short-term. It means that these forests can bounce back. But if you push those forests long enough, resilience won’t be enough. What you need is adaptation.”

Six, DellaSala and their colleagues also caution that too much prescribed burning can leave soils ill-equipped to support regeneration. And they contend that post-fire restoration often removes dead trees vital to a functioning ecosystem and can turn into a “salvage logging” cash grab for industry to harvest saleable wood from forests.

“What you’re doing is setting up that forest for big future problems,” Six says. “People have a tendency of looking at forests kind of like corn. It’s just a bunch of trees standing around out there, and they don’t see beyond that. There’s interactions and functions and processes that need to be in place, and you have to support those, or you begin to lose your forest.”

The critics admit that active management can be helpful in certain circumstances — when nonnative species have taken over, for example, or making up for places with a natural fire “deficit.” But by and large, they urge caution.

“It’s not that their research is dead wrong,” DellaSala says of proponents of active management. “It’s just too narrow and assumes that the costs are easily handled by ecosystems.”

The fear seems to be that any broad acceptance of active management will quickly trigger a slide toward misuse, in which ecosystems will ultimately suffer.

Hessburg says he understands the concern to a point. The widespread loss of forests, and in particular, old-growth trees for timber, in the latter half of the 20th century was alarming, he adds.

Researchers measure an old-growth tree as part of a modeling study at Emerald Bay State Park in California. Image © Hugh Safford/UC Davis.

“Liquidating primary forests is probably not the best thing we ever did,” Hessburg tells Mongabay.

Still, he argues that mistrust of the tools is “not a strategy” for addressing the heightened risk and severity of fire.

“There’s also the other side that good can come from work,” Hessburg says. “The work of human hands can be negative or can be positive. We get to choose how we do it.”

Hessburg notes that keeping fire out of these forests was in itself a form of active management. That’s something that needs to be rectified with the tools at our disposal, says Bryant Nagelson, a research associate at the University of Nevada, Reno.

“We can’t protect that area without trying to undo the form of active management” — that is, fire exclusion — “that’s been in place for so long,” Nagelson says.

Now, after cataloging decades of past missteps and trying to sort out the best path forward, Hessburg says he’s convinced that only active management, applied carefully and thoughtfully, will allow dry forests to persist in the Anthropocene. Leaving them to their own devices won’t work, he says.

“If it was 1800 and lands were being allowed to burn, and we weren’t tucked into the wildlands with our homes, that’d be an OK thing,” Hessburg says, “but it’s not.”

Research has shown that people are responsible for the great majority of wildfires in the U.S. Image courtesy of Climate Central.

Banner image: A crew of firefighters fights the Vees Fire near Ten Sleep, Wyoming, in July 2025. Image by Trae Holliday via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

John Cannon is a staff features writer with Mongabay. Find him on Bluesky and LinkedIn.

Update: This version of this article reflects Dominick DellaSala’s current affiliation.

Citations:

Balch, J. K., Bradley, B. A., Abatzoglou, J. T., Nagy, R. C., Fusco, E. J., & Mahood, A. L. (2017). Human-started wildfires expand the fire niche across the United States. Proceedings of the National Academies of Science, 114(11), 2946-2951. doi:10.1073/pnas.1617394114

Lindenmayer, D., Zylstra, P., Hanson, C. T., Six, D., & DellaSala, D. A. (2025). When Active Management of high conservation value forests may erode biodiversity and damage ecosystems. Biological Conservation, 305, 111071. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2025.111071

Prichard, S. J., Hessburg, P. F., Hagmann, R. K., Povak, N. A., Dobrowski, S. Z., Hurteau, M. D., … Khatri-Chhetri, P. (2021). Adapting western North American forests to climate change and wildfires: 10 common questions. Ecological Applications, 31(8), e02433. doi:10.1002/eap.2433

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Related:

Here are more “ET’s” recorded from around the planet the last couple of days, their consequences, and some extreme temperature outlooks, as well as any extreme precipitation reports:

Here is More Climate News from Saturday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)