The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track planetary extreme, or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😉

Main Topic: Why Some Ominous Forecasts Don’t Pan Out…Case in Point Sara

Dear Diary. The GFS meteorological model did great with Milton, which developed the system such that it became a major hurricane in the Bay of Campeche then barreled the thing into central Florida, correctly forecasting the event more than a week out in time. So, when forecasters including yours truly saw the GFS and other guidance consistently forecasting a hurricane in the Caribbean moving towards Florida in early November, we jumped on it:

Sometimes climate change related disasters don’t pan out…thank goodness! Still, all of that pent up record warmth from sea surface temperatures in the Caribbean will wait to be tapped in 2025.

Today we will get into the nuts and bolts of why Sara remained a weak system and why stronger GFS ensemble members were busts. Yes, Sara humbled the old Climate Guy. Even after 40 years of meteorological experience, I can sometimes make a bad forecast, although I did mention that Sara might weaken if it interacted with Central America. Here is Tomer Burg’s informative blog:

http://arctic.som.ou.edu/tburg/blog/post.php?date=20241116

Tropical Storm Sara: What Went Wrong?

Tomer Burg • 16 November 2024 • Current Weather

Post Highlights

Tropical Storm Sara is currently producing torrential rainfall and flooding across portions of Central America, and is expected to make landfall in Belize as a weak tropical storm before dissipating inland, with remnant moisture spreading into the southeast U.S. But this was not the original forecast – just a few days ago, many models were consistently showing a hurricane or major hurricane approaching Florida. This post looks at why models showed that outcome, and where the forecast went wrong.

Background: Models Show a Hurricane

Let’s say you’re a weather forecaster/meteorologist who communicates the latest forecast to the public, and has an audience from Florida that follows your updates. You know it’s been a rough year for Florida – just in the last 2 months, Hurricanes Helene and Milton caused devastation in parts of the state, not to forget mentioning Hurricane Debby in August. Just a few days ago, the Keys were missed from the worst of Hurricane Rafael, which passed not too far to the west. Naturally, people will be concerned if a hurricane is mentioned again in the forecast.

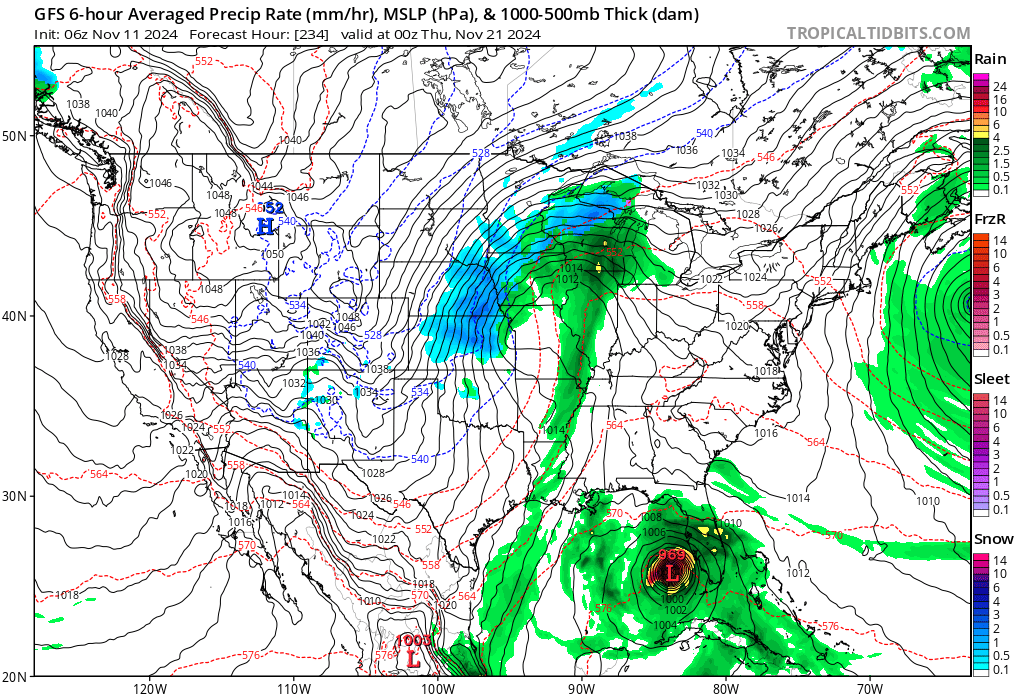

Trend in the last 7 runs of the GFS up through the evening of November 12, 2024.

Now let’s say it’s November 12. You check the Global Forecast System (GFS) model, as you typically do, and see it showing a major hurricane approaching the same part of Florida affected by Milton and Helene. You already see posts on social media using just that GFS run saying “MAJOR HURRICANE SARA expected to HIT FLORIDA, you have been WARNED!!”, and think to yourself “it’s just one run of a deterministic model, this is just clickbait”. You are also initially skeptical as you’ve seen these exact same clickbait posts for Hurricane Rafael, which ended up not directly affecting Florida with hurricane conditions.

But you still want to check more data, just to know for sure if it is clickbait or not. So you look at the trend in the last 7 runs of the GFS – and to your surprise, every single run shows a hurricane hitting the same region of Florida! Yes, it is still over a week away, but that run-to-run consistency gets you to start taking this scenario a bit more seriously. You also note how consistent not only the signal for a hurricane is, but also the part of Florida that it hits.

Your next thought is to check other models to see if the same signal is still there. Even if the GFS is consistent run-to-run, it can be consistently wrong sometimes. It does sometimes have a false alarm bias – meaning it spins up tropical cyclones in the long range that either don’t develop, or are much weaker than it showed. This does have precedent – take this example from May 2022 of a fantasy GFS hurricane that never developed.

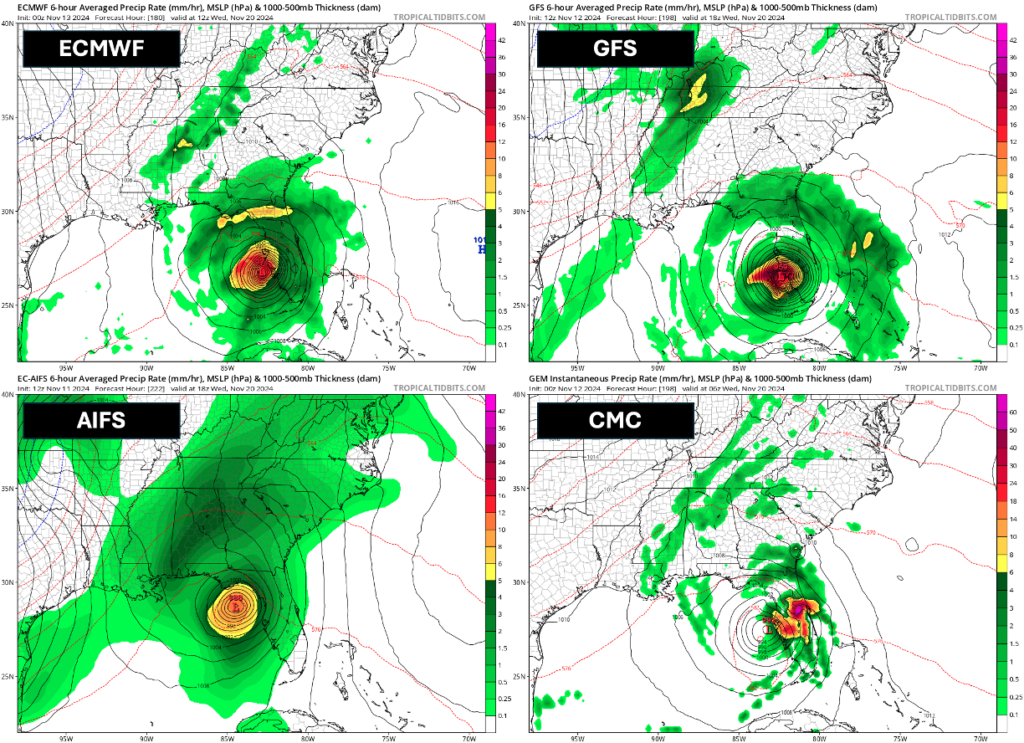

You start going through all of the other global deterministic models. The CMC (Canadian model) shows a sheared tropical storm. ICON (German model) shows a hurricane entering the Gulf of Mexico en route to Florida at the end of its run. Most alarmingly, the ECMWF (European model), which sometimes underestimates hurricanes in the medium range, also shows a major hurricane approaching Florida in multiple runs, and ECMWF’s AI model (AIFS), which has done well with identifying potential hurricanes at longer lead times this year, also shows a hurricane affecting Florida.

So it’s not just the GFS… all of these deterministic global models on November 11-12 also showed a hurricane affecting Florida.

After looking at all of these signals, you become convinced there is a legitimate signal here and not a fluke. Some people might see this and be convinced this is enough of a signal to raise alarms for a likely Florida hurricane landfall. But you might still not be fully convinced, and at this point, think to yourself “these are just deterministic models – what do ensembles show?”. And this is a fair question to ask. Deterministic models are only one possible outcome – there is always uncertainty in the exact initial state of the atmosphere used to initialize the models, and uncertainty in the small-scale physical processes that are too small to be explicitly calculated by weather models (these are called “parameterizations”). Ensembles apply perturbations to the initial state of the model, and these physical processes, to account for that uncertainty, and the result is a larger range of possible outcomes.

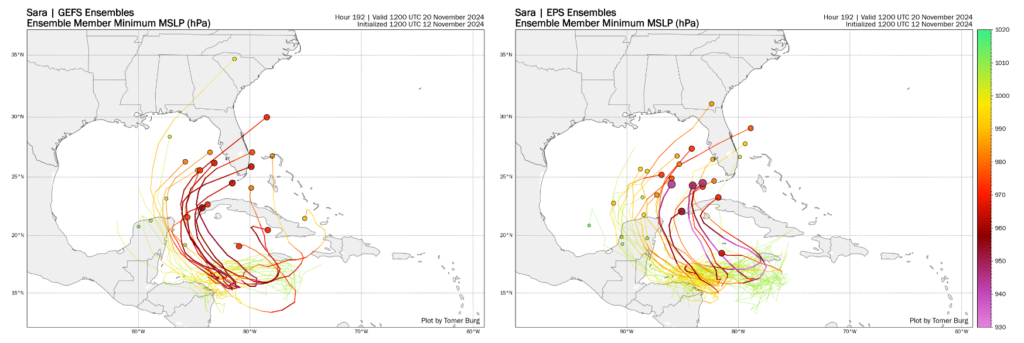

You check the GFS ensembles (GEFS), which is a 31-member ensemble, and the ECMWF ensemble (EPS), which is a 51-member ensemble. Many ensemble members also show a major hurricane approaching Florida. There is more variability than the deterministic runs, however – some ensemble members have the hurricane staying south/east of Florida, others have a tropical storm instead of a hurricane approaching Florida, and there’s a small but noticeable subset of ensemble members that don’t even bring the storm to Florida. Instead, they just have a weak storm lingering near the Central American coast.

GFS (left) and ECMWF (right) ensembles with many members showing a hurricane approaching Florida. Darker colors and larger dots indicate a stronger storm, while brighter colors and smaller dots indicate a weaker storm.

The Dilemma: At this point, you may be tempted to brush those weak ensemble members off – you might think to yourself “these are global ensembles, they have a lower resolution than deterministic models meaning they struggle to resolve small-scale processes associated with hurricanes”. You look at the Caribbean which has very warm water temperatures and low vertical wind shear, factors which are favorable for rapid intensification of a hurricane. You might think back to Hurricane Milton, where global models and ensembles were too weak with the storm, or Hurricane Oscar, where global models completely missed the development of a small but intense storm.

You may still be tempted to brush those members off… but should you? You think back to other times when models were too strong with a hurricane, or showed a signal for a hurricane that didn’t actually happen. But you think practically, about how Florida is still recovering from the devastation of multiple hurricanes, and realize that a lot of lead time is needed to prepare for another hurricane should it actually affect Florida. You start to weight the pros and cons of how much you should warn people about a potential hurricane over a week away.

If you warn too strongly about a hurricane too early and a storm doesn’t happen, you risk being seen as exaggerating a forecast for engagement, or worse yet, preying on people’s fears. If you wait until there’s a stronger forecast signal and warn too late, and the hurricane does hit Florida, you risk giving people and decision makers too little time to prepare, or worse yet, be accused of withholding important information from the public – after all, everyone could see that models showed a hurricane over a week away.

Before we go into what is actually happening and where things went wrong, let’s take a look first at the meteorology behind this storm, why models consistently showed a major hurricane approaching Florida over a week away, and why there was still a small subset of models that didn’t show a hurricane.

Meteorology of Sara’s Forecast

For the more technical portion, continue to read Toma’s blog:

http://arctic.som.ou.edu/tburg/blog/post.php?date=20241116

Here are more “ETs” recorded from around the planet the last couple of days, their consequences, and some extreme temperature outlooks, as well as any extreme precipitation reports:

Here is more brand-new October 2024 climatology (More can be found on each past archived daily November post.):

Here is More Climate News from Monday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)