Tuesday December 24th… Dear Diary. The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track United States extreme or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😉

Main Topic: I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas… What Will Happen To These As The World Warms?

Dear Diary. I can only remember one time living in Atlanta in which there was snow on the ground on Christmas Day, and I’ve been here since the colder decades of the 1970s and 1980s. That year was 2010. Climatologically there are some places that don’t see much snow or never see the white stuff on Christmas. In this day and age of global warming what might be the trend for more marginal areas that traditionally have a good chance for seeing snow on Christmas such as the Ohio Valley?

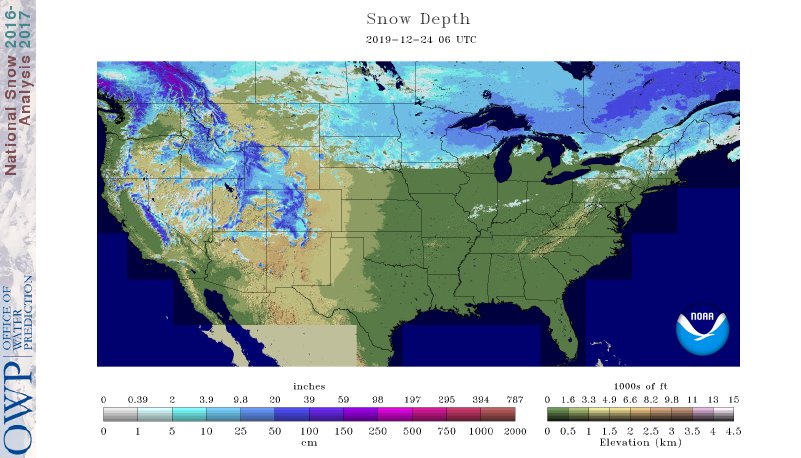

This year we are seeing a notable December warm spell east of the Rockies that will be coinciding with Christmas. Bah Humbug. Here is current U.S. snow cover on Christmas Eve:

Outside of higher elevations of the West only the northern Plains and northern New England will be seeing a white Christmas in 2019. Over the years I’ve seen overall trends for less snow cover across the lower 48 states on Christmas, and this year will be no exception.

For today’s main topic I ran across a Smithsonian article about what we can expect in association with future white Christmases the next few decades:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-happens-to-white-christmases-as-the-world-warms1/

What Happens to White Christmases as the World Warms?

Although more winter precipitation will fall as rain because of climate change, don’t say goodbye to snow just yet.

- By Andrea Thompson on December 23, 2019

Credit: Getty Images

With that famous song, sleigh rides and snowmen who magically come alive, so much of the cultural imagery associated with Christmas features a glistening carpet of snow.

But as rising global temperatures start to dull winter’s bitter edge, will the proverbial White Christmas become just a bit of Yuletide lore? Although logic would seem to suggest that warming would mean less snow, the impact of climate change on where—and how much—snow falls is more complicated than that. Climate science cannot say whether there will be snow on the ground in Boston or Chicago on Christmas Day 2050, but there are some general trends scientists expect to see—and also some less intuitive ones.

One reason the influence of climate change on snow is difficult to untangle is that snow can be a very localized phenomenon. One town may be socked in, whereas houses just a few miles away get only a dusting. And the chances of a given location having snow on the ground on any particular date, such as December 25, can vary widely from year to year outside of the most northern locations (in the Northern Hemisphere, where most related research has been conducted). Those traits, along with variations in how snow is measured, make compiling snowfall data to look for trends a delicate business. “That’s why you look at multiple years, at multiple stations. Never trust just a couple of measurements,” says New Jersey state climatologist David Robinson, who studies snow and climate at Rutgers University.

On top of those issues, there are more ingredients to consider when understanding precipitation trends than there are for temperature, because wind patterns in the atmosphere come into play. And snow has even more constraints than rain, as it only materializes when temperatures fall below the freezing point.

That temperature dependence means that in a warmer future, “you’re going to have more cases where temperatures are just above that magic mark,” Robinson says, meaning more winter precipitation will fall as rain. This trend will start in more southerly locations (in the Northern Hemisphere), and at lower elevations, and will gradually progress northward as the planet heats up. In places where winter temperatures do stay below freezing, however, more snow could actually fall because warmer air holds more moisture. There is already some evidence backing both of these expected trends, Robinson says, with regions such as the Upper Midwest recording more snow in recent years and the southern reaches of the U.S. seeing declines.

That second point about moisture in a warmer atmosphere is behind one of the quirks scientists have uncovered: although snow will become less common overall, extreme snowfalls will decline at a slower rate than average ones, so that blockbuster snowstorms become a bigger proportion of all snow events. M.I.T. atmospheric scientist Paul O’Gorman explained this quirk in a 2014 study in Nature, noting that extreme snowfalls happen in a narrower temperature band than snow overall—temperatures need to be cold enough to freeze precipitation, but not so cold that the atmosphere dries out. So warming temperatures chip away faster at the broader temperature range in which all snow occurs than they do at the range for extreme snowfalls.

Warming may also boost—and change the timing of—a particular type of snowfall: lake-effect snow, which in the U.S. is mostly commonly associated with the Great Lakes. Lake-effect snow happens when cold Canadian air pushes down over the lakes when they are still relatively warm and not yet iced over. This cold air causes the lake water to evaporate, which warms the air above the lake surface. That air rises, cooling again as it does so; any moisture in it can then freeze and fall as snow. Rising temperatures will keep lakes warmer, providing more moisture when cold winds happen to blow overhead.

Those warmer temperatures will also keep the lakes ice-free for longer into the fall, expanding the lake-effect season. Climate models suggest that trend will not last forever, though, as air temperatures could eventually become too warm to support snow. But while it does, it could mean that areas where lake-effect snow is common could see more Christmas snow if conditions are right.

Yet on a broader scale, picking out any seasonal trends in snow extent—the area covered by snow—is more difficult. There is a clear trend toward earlier melt in the spring, which was particularly evident during the recent extremely warm years in the western U.S. “Irrefutably, [snow extent] is declining in the spring,” Robinson says. But for fall and winter “there’s no clear signal,” he adds. “There’s no glaring change … when it comes to Christmas-time snow.”

The bottom line, he says, is that we will see snowstorms in the future, and some of those will coincide with Christmas. “There’s still going to be winter,” Robinson says. “I think people can expect change, but if they’re looking for the total demise of snow, I think that’s premature.” Rights & Permissions

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Andrea Thompson

Andrea Thompson, an associate editor at Scientific American, covers sustainability.

Credit: Nick Higgins

Recent Articles

- Switching to Renewables Can Hurt Vulnerable Groups–Unless Utilities Plan Ahead

- New Zealand Eruption: The Inherent Risk in Visiting Volcanoes

- Warming Will Cost Rich and Poor Countries Alike

Well, here is wishing you and yours a Merry Christmas snow or no snow.

Here is more climate and weather news from Tuesday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article.)

(If you like these posts and my work please contribute via the PayPal widget, which has recently been added to this site. Thanks in advance for any support.)

Guy Walton- “The Climate Guy”