The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track planetary extreme, or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😉

Main Topic: How Do You Picture a Heat Wave?

Dear Diary. I’ve been reporting about heatwaves in earnest ever since I started this website in the spring of 2017. I’ve seen a lot of feedback on pictures that are used to report heatwaves from big corporate media, such as the New York Times all the way down to small entities like my guyonclimate.com. Anyone reporting on heatwaves has a problem using pictures in association with the event since heat has been described as being an invisible killer. Showing a picture of children playing in a water fountain or at the beach is a no no because that action would depict a problem that can easily be solved by a cool splash. Most people who succumb to heatwaves are loners who do not have good access to cool fountains or even air conditioning. So, should we show dead people after they have been discovered and pegged with dying from heat? That action would be a bit too morbid.

Other weather phenomena like pictures and videos of tornadoes and their aftermath are easy to use. Heat waves are much stealthier, though. Here is an essay written by my friend Bob Henson describing the conundrum that news media people have when trying to use pictures to cover a heatwave:

How do you picture a heat wave? » Yale Climate Connections

How do you picture a heat wave?

From beaches to morgues, illustrating a heat-wave story is riddled with challenges.

by BOB HENSON

JUNE 26, 2024

A woman gets water from a fountain in Manhattan on June 21, 2024, the first full day of summer and a sweltering afternoon in New York. The city’s Central Park recorded highs at or above 91 degrees Fahrenheit from June 20 to 23, the longest four-day stretch of such intense June heat since 2008. Low temperatures failed to dip below 72°F from June 19 through 24, the earliest in the year such a warm-night stretch has occurred in 155 years of official New York weather data. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

It’s never easy to capture the feeling and the impact of a dayslong stretch of intense heat in photographs. Heat waves often spawn or exacerbate other weather disasters — wildfires and crop-snuffing drought in particular — and those are much easier to capture visually. But as Earth’s climate keeps warming from human activity, the direct effects of intense heat on human bodies are gaining ever more attention, and these effects are devilishly difficult to convey in a photo.

The long-simmering challenge of illustrating heat waves in news stories came to a boil again late this spring, as major heat episodes took many hundreds of lives in multiple corners of the world. In a Substack post on June 20, the eminent writer and climate activist Bill McKibben lit into “lazy” photo editors. McKibben called out the New York Times for a tranquil, people-lolling-on-the-grass photo that accompanied a recent roundup of global heat disasters. He added:

Over the last few years numerous professions have worked hard to get more serious about the crisis we’re in — even weather people, who have increasingly taken to telling the truth (though not always with happy results). The men and women who pick images for stories are still stuck back in some 1950s notion of a heat wave, when they were not as hot, came less frequently, and resulted in people going to the beach, not the hospital. Pictures matter: if every story about a war was decorated entirely with pictures of people getting medals, we might have even more wars than we do.

McKibben’s valid point notwithstanding, the problems with illustrating heat waves aren’t easy to fix, for multiple reasons. Especially at city and regional news outlets, producers and editors want fresh, timely, local images whenever possible. Stock photos of people in heat waves don’t fill this particular need, and it can be surprisingly tough to find photos that do.

For years, the group Covering Climate Now has urged journalists and photo editors to do better when they report on heat waves. The group recently posted an excellent guide with tools for reporting on this summer’s extreme heat, including multiple modes of bringing in crucial context. But even this well-crafted guide doesn’t offer specific tips on how best to put a photographic spin on a heat wave.

Plenty of photos are routinely gathered from other weather-related catastrophes with strong climate-change links, such as hurricanes and wildfires. That’s largely because such disasters often produce catastrophic damage that leads to death and injury, so it’s a simple matter to use dramatic damage photos as a proxy for human impacts.

The worst heat waves are more like neutron bombs: They kill people while leaving buildings standing. And most of the deaths occur beyond the gaze of observers, including photographers.

The lawn of the newly completed Nebraska State Capitol provided a resting place for Lincoln residents trying to escape the heat in July 1936, near the peak of the 1930s Dust Bowl. During that decade, the human influence of over-plowed, denuded landscapes intensified the effects of a multiyear drought across vast parts of the central United States, leading to many heat records that remain in place today. Lincoln’s hottest daily minimum on record and its all-time high both occurred on July 25, 1936, with 91°F and 115°F, respectively. (Image credit: History Nebraska Collections)

The solitary experience of heat illness

In his classic book “Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago,” which chronicles the horrific heat event in July 1995 that killed more than 700 people, Eric Klinenberg memorably explored the pathos of the event. Many of the victims died in apartments without air conditioning, or with AC turned off to save money, and with windows closed or locked. Klinenberg told me: “If you look closely at the police reports, or the medical autopsies, they’re just horrific. These are isolated, lonely, painful deaths.”

It may be impossible for any picture to distill that agonizing experience as strongly as words can. Indeed, there are surprisingly few photos at wire services or history archives that deliver a full sense of what happened in that awful Chicago summer.

A Cook County medical examiner pushes a gurney on July 16, 1995, carrying the body of one of more than 700 people killed by heat-related causes in Chicago. Many of the victims were not discovered until after the worst heat had passed. At one point, bodies were being stored in refrigerated tractor-trailers. (Image credit: Brian Bahr/AFP via Getty Images)

In my book “The Rough Guide to Climate Change” (now “The Thinking Person’s Guide to Climate Change”), I went with a wire-service photo of a bagged body being moved toward a refrigerated truck, similar to the one above. Grim, to be sure, but it showed both a victim and a responder and thus helped convey the human reverberations of the event.

In recent years, perhaps because of a higher priority on reader sensitivity and subject privacy — especially in the realm of health — such photos of body bags and morgues are rarely used.

Sadly, and tellingly, some of the most compelling photos of Americans truly suffering in heat waves have been of people without housing being assisted or taken to shelter. In Maricopa County, which includes Phoenix, close to half the documented heat deaths in recent years have been among unhoused residents.

After being disabled in a motorcycle accident, Shy (her street name) has been living without permanent housing for years. In May 2023, she and her dog, Tinkerbell, were struggling to survive in the Zone, one of the largest homeless encampments in the U.S., where the temperature can reach 119 degrees. (Photo credit: Osha Davidson)

Read: For unhoused people in America’s hottest large city, heat waves are a merciless killer

The growth in municipal cooling centers is one of the great successes in U.S. heat-wave response over the last 20 years. Yet timely photos from cooling centers don’t seem to make the news often. Maybe it’s because such centers, which basically consist of large groups of people resting in an air-conditioned space, don’t scream “heat impacts” at first glance. And privacy may again be a factor.

Natasha Bertram cools off with her daughter Pepper at the beach in Chicago’s Humboldt Park on June 17, 2024. The city set a daily record high of 97 degrees Fahrenheit. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Life may be a beach, but what’s a heat wave?

It’s indeed a timeworn choice — and granted, sometimes a lazy one — to show people at the pool or the beach when covering the local or regional impacts of a heat wave. The irony is that splashing in a large body of water is a perfectly valid way to adapt to intense heat. It’s also one of the few heat-coping mechanisms that are out in the open and easy to capture in a photo or video.

Though there’s some obvious privilege in being able to find your heat relief while poolside or beachside, it’s hardly an activity that’s limited only to wealthy folks. In many urban areas, there’s a longtime parallel: fire hydrants being turned on to provide heat relief for those who can’t get to a body of water.

Eduardo Velev cools off in the spray of a fire hydrant during a heat wave on July 1, 2018, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Photo by Jessica Kourkounis/Getty Images)

So even if a beach or pool photo seems off-key or weirdly upbeat when accompanying a heat-wave story, it’s still a legitimate part of what’s happening. Indeed, there are plenty of ways to mitigate and adapt to climate change that can be both enjoyable and helpful, from bicycling to growing one’s own food.

Workers dump blocks of ice at a pool amid extreme heat at the Hidden Sanctuary Resort on May 4, 2024, in Marilao, Philippines. Extreme heat led to the closing of schools in the Philippines, with students reverting to remote learning; official drought declarations occurred in about half of the country’s provinces. (Image credit: Ezra Acayan/Getty Images)

What’s crucial is not to expect a lighthearted “day at the beach” photo to carry the full weight of illustrating a truly catastrophic heat wave, much less the invisible forces of climate change that can bolster it.

Imaginative photographers look for people on the street or in an outdoor work setting who may be using water bottles, sun-blocking hats, and other techniques to stay cooler and safer, yet who may still be profusely sweating and visibly uncomfortable. It’s a topic taking on more resonance than ever, as some states, including Florida and Texas, have been clamping down on local requirements designed to ensure worker safety during heat waves.

Construction worker Dennis Jenkins dumps water from his hard hat over his head while working at the construction site for Nationals Park in Washington, D.C., on July 10, 2007. The high was 96 degrees Fahrenheit that day after a record high of 97°F the day before. (Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images)

When air pollution accompanies a heat wave — something that’s often the case, and often a major contributor to deaths and health impacts — a milky sky or a copper-colored sun can help set the scene. The smoke from Canadian wildfires stoked by record heat and drought led to memorable U.S. imagery in the late spring and summer of 2023.

Anthony Rizzo of the New York Yankees jogs to the dugout during the second inning against the Chicago White Sox at New York City’s Yankee Stadium on June 6, 2023, under smoky skies from Canadian wildfires. Outdoor exercise is not recommended when air quality is poor. (Image credit: Sarah Stier/Getty Images)

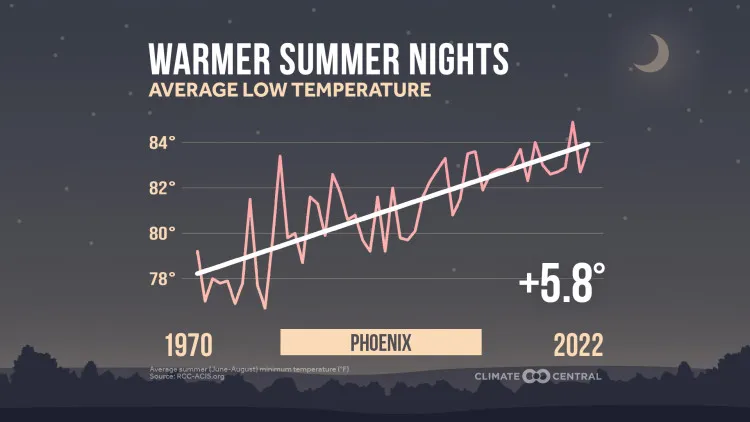

Cleverly designed graphs and charts can also add variety to heat-wave coverage while bringing home important science points. Climate Central, a partner of Yale Climate Connections, caters to broadcast meteorologists and other communicators with a wide array of lively, scientifically vetted graphics.

The average daily low temperature in Phoenix, Arizona, during the summer months of July through August has climbed almost 6 degrees Fahrenheit since 1970, from just above 78°F to around 84°F. Hot nights are among the most dangerous aspects of a multi-day heat wave, as they give vulnerable people little chance to cool down. (Image credit: Climate Central)

Making a visceral experience more visible

How we picture weather extremes in a changing climate is a hugely important topic of conversation, and it’s good to be giving heat waves some careful thought in that context. This is especially the case given the outsized and increasing threat that intensifying heat (including “humid heat”) poses to human health.

The thick, stifling atmosphere of a heat wave may never lend itself to mind-blowing photography. But given the resources and opportunity, talented photographers can still find ways to show, or at least imply, the misery and danger that a heat wave brings. And skilled editors can do their best to incorporate imagery from across the full spectrum of heat-wave effects.

That might even include the occasional beach photo — as long as it’s made clear through accompanying images, and in the narrative or captions, that not everyone gets to cavort in the sun when the heat hits.

We help millions of people understand climate change and what to do about it. Help us reach even more people like you.

Bob Henson’s How Do You Picture a Heat Wave? was first published on Yale Climate Connections, a program of the Yale School of the Environment, available at: http://yaleclimateconnections.org. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 license (CC BY-NC-ND 2.5).

BOB HENSON

Bob Henson is a meteorologist and journalist based in Boulder, Colorado. He has written on weather and climate for the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Weather Underground, and many freelance… More by Bob Henson

Here are more “ETs” recorded from around the planet the last couple of days, their consequences, and some extreme temperature outlooks, as well as any extreme precipitation reports or outlooks:

Here is More Climate News from Friday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)