The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track planetary extreme, or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😜

Main Topic: Jane Goodall’s Thoughts: ‘Hope Isn’t Just Wishful Thinking’

Dear Diary. On October first the world lost a premier scientist who was a renounced environmentalist whose main focus was the study of primates. Jane Goodall was legendary in her younger years for her long stints in Africa’s bush country making friends with gorillas and chimpanzees. She also was outspoken on climate change, encouraging everyone to do their part to help solve the problems behind carbon pollution. At age 91 when she passed Jane was still in the lecture circuit. I’d definitely say that this was a life well lived.

Here are more details from the New York Times:

Jane Goodall’s Thoughts for a Reporter: ‘Hope Isn’t Just Wishful Thinking’ – The New York Times

Jane Goodall’s Thoughts for a Reporter: ‘Hope Isn’t Just Wishful Thinking’

A Times correspondent who interviewed Dr. Goodall recalled their conversations about the state of the planet.

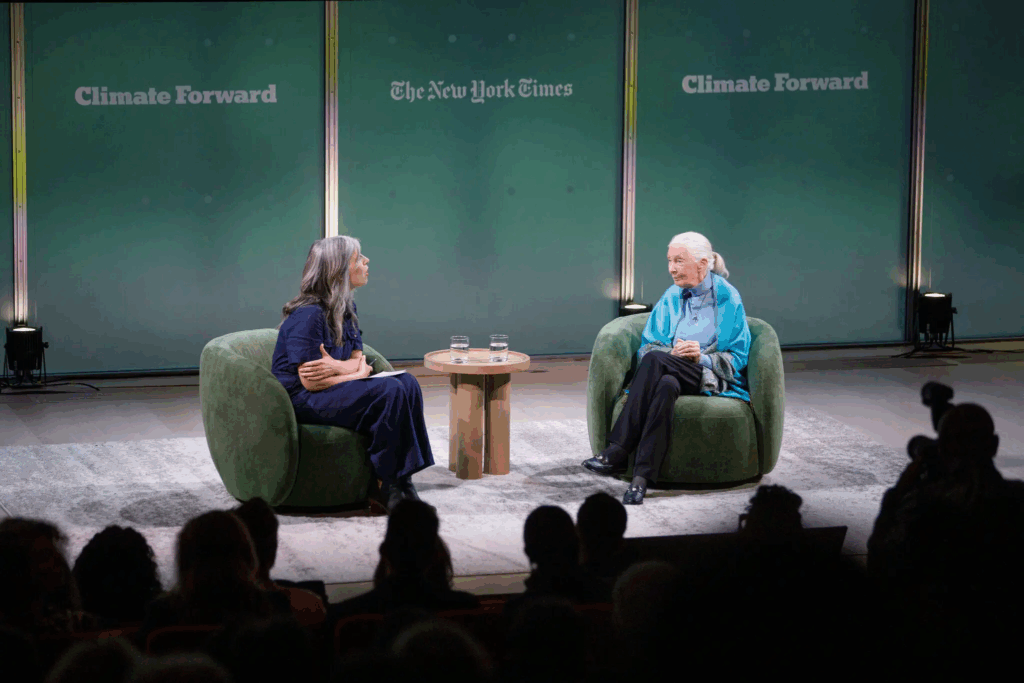

Jane Goodall, right, speaking with Catrin Einhorn at The New York Times’s Climate Forward event in September 2024. It was one of two interviews they did last year. Credit…Benjamin Norman for The New York Times

Oct. 1, 2025

On the day Jane Goodall turned 90, I sat down at a small table with her. It was April 2024, and she was in Manhattan to promote a partnership with a jewelry company, Brilliant Earth. The company was making a $100,000 donation to support the Jane Goodall Institute, and she was giving her name to an eco-friendly line of necklaces, rings and earrings. The gold would all be recycled and the diamonds would come only from labs. No mining involved.

People buzzed around; a lunch would be served, and fashion influencers were on hand. Dr. Goodall looked small and tired amid the hubbub.

I knew the question I wanted to start with.

“When you woke up this morning, on your actual 90th birthday, what was the first thing you thought?” I asked. The room was so loud that I had to lean forward to hear her response.

“That I wish I was somewhere else,” she said.

It wasn’t the answer I expected. Relistening to the tape of our interview on Wednesday, the day she died, I hear my voice change from cheery to concerned.

“Well, you know, I like being out in nature,” she explained. Then she told me about all the birthday greetings she woke up to, and how she thought of her family and friends. This day wasn’t about that, she said, seeming a little sad but resolved.

“This birthday is about my mission, which is getting the word out to people around the world and raising money for our projects,” she said.

Dr. Goodall was laser-focused on that mission, people close to her told me. She wanted to do everything she could to make sure her institute could continue its conservation and educational work after her death. And she seemed committed to using her fame — more than fame, the reverence she often inspired in people — to try to get the world to take action on climate change and biodiversity loss.

“That’s why I’m traveling 300 days a year,” she told me. “It’s no good just talking about what should be done. We’ve got to flipping well do it.”

Ever since she first attracted attention as a young researcher who documented a chimpanzee using stems and twigs as tools for nabbing termites, Jane Goodall seemed more than willing to let herself be used for her causes.

For example, she often told an anecdote about her legs. There they were in photographs of her in National Geographic in the 1960s, a young woman in the field in Tanzania with a ponytail and wearing shorts. Her legs triggered comments. They were deemed attractive. Recounting the story this year on the podcast “Call Her Daddy,” she told of how some jealous male scientists groused that she was getting cover stories and money for research because of those legs.

“If somebody said that today, they’d be sued, right?” she said. “Back then, all I wanted was to get back to the chimps. So if my legs were getting me the money, thank you, legs!” she said, patting her thigh.

“And if you look,” she added, “they were jolly nice legs!”

But in April last year, she told me she was exhausted, and she looked it. I offered to cut the interview short. She instructed me to keep asking questions.

“It means I can sit here and talk to you instead of going mingling,” she said with a smile.

So, we talked more about the United Nations biodiversity conference coming that fall. I asked her about a message of hers that always struggles to gain traction: the need to consume less. I had read about how she turned the three R’s (reduce, reuse, recycle) into the five R’s, adding refuse at the beginning and rot at the end. She said she believed that a circular economy, one mimicking nature’s zero-waste cycles, was key to getting us out of the ecological mess we’ve made.

She also said that children were central to persuading adults to live more ethically. I already knew how much Dr. Goodall loved talking about Roots & Shoots, her institute’s youth program, and she took the opportunity to highlight it.

We talked about journalism. She thought it was imperative for reporters to share the untold stories of people who are working hard to make a difference.

“Not just the good news story, but how that good news story fits into alleviating the doom and gloom,” she said.

We didn’t talk about death, but it’s something she wrote and spoke about quite a lot. In “The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times,” which she wrote with Doug Abrams, she called death her next great adventure.

I interviewed Dr. Goodall again a few months later, this time onstage at The New York Times’s 2024 Climate Forward event. It was a year ago last week.

My favorite memories of that day were sitting in the greenroom with Dr. Goodall before the interview. We chatted about her Welsh grandfather and my Welsh mom. This time, she seemed full of quiet energy. She was gentle and sharp, all at once.

Onstage, I knew what my last question would be.

Preparing for that interview, I had asked virtually everyone I came across, from all walks of life, what they wanted to know from Dr. Goodall. Again and again, the answer was the same: They wanted to know where they could find hope. But I didn’t want to ask that question, because she has answered it in at least two books on the subject. So I asked her about balancing hope — which she found in human intellect, in the resilience of nature, in the power of young people and in the indomitable human spirit — with false hope, sometimes called “hopium.”

She didn’t hesitate.

“Hope isn’t just wishful thinking,” she said, telling us to imagine a long, dark tunnel with a little star at the end representing hope.

“There’s no good sitting at the mouth of the tunnel and wishing that that hope would come to us,” she said. “We’ve got to roll up our sleeves. The Bible says, gird your loins. I love that. I’m not quite sure what it means, but let’s gird our loins. And we’ve got to climb over, crawl under, work around all the obstacles that lie between us and the star.”

Catrin Einhorn covers biodiversity, climate and the environment for The Times.

See more on: Jane Goodall

More:

Here are more “ETs” recorded from around the planet the last couple of days, their consequences, and some extreme temperature outlooks, as well as any extreme precipitation reports:

Here is More Climate News from Friday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)