Tuesday August 11th… Dear Diary. The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track United States extreme or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😉

More Heat Leading To Stronger Storms…The Case Of The 8/10/2020 Derecho

Dear Diary. If you have taken an introductory physics class you you know that the more energy you put into a system the more mass can be moved. In the case of the atmosphere, in the troposphere heat energy can lead to more ferocious storms, which move gas or produce high winds. Such was the case yesterday in the Midwest due to a ferocious derecho. This was an impressive radar of the system moving through Illinois:

Did climate change have any effect on yesterday’s ferocious storm system? Probably. I did note slightly above average heat feeding into the thing from the south:

I contend that if there had not been quite as much heat in the South the storm system would have been weaker or taken on a more southern route. Of course, derechos have formed over North America well before the last stone age, but I doubt we saw any as far north as the Midwest area during the last ice age. It was just too cold with dewpoints too low, even in summer. We don’t have a time machine to verify this assumption, though.

Climate change is definitely leading to hotter summers, so there is an abundance of unstable potential energy over much more real estate compared with cooler times decades ago. We should see more derechos further north in time as our climate continues to warm.

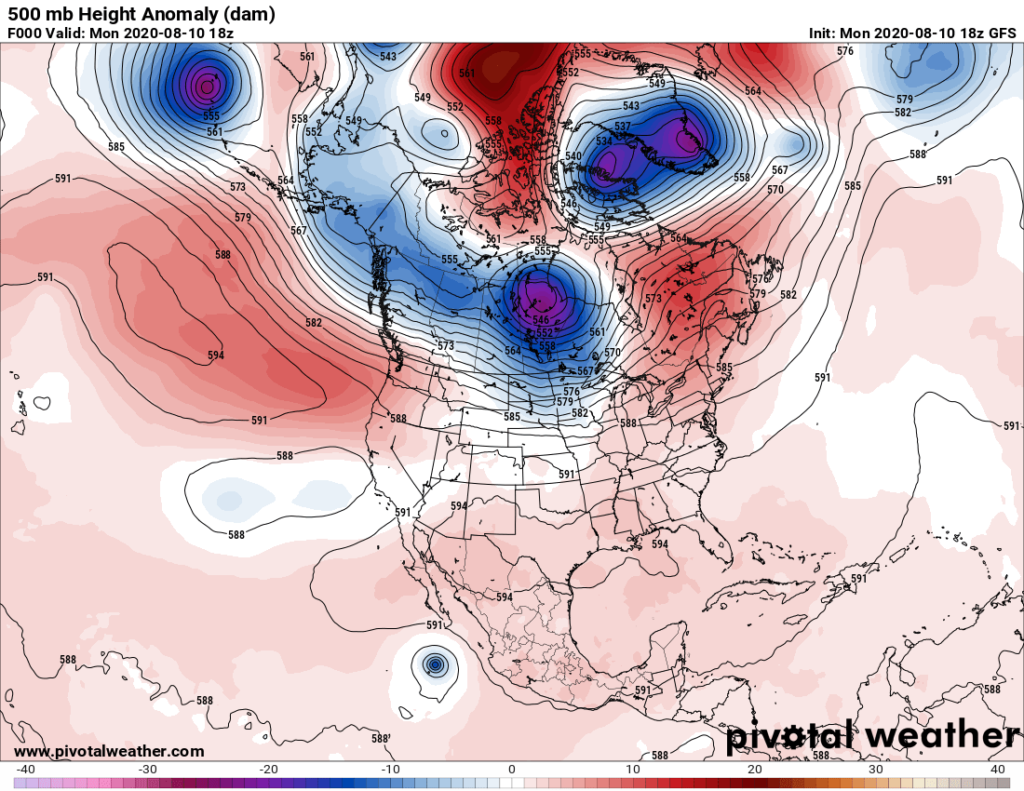

Aloft to get a derecho we need a strong heat dome to the south and west of a subtle digging jet as can be picked up on weather charts. Here is the 500 millibar setup from 12Z Monday:

In the above image we see a slight trough extending from the cold vortex in central Canada into Iowa, western Missouri, and southwest into Oklahoma. This was a “short wave” responsible for triggering the derecho. The short wave weakened the heat dome to its southeast carving a path for the storm system to follow. Typically we see an orientation of a stronger part of a heat dome or ridge from the southern Plains into the Southwest, with the weaker part of the ridge extending into the eastern and southeastern U.S. to get a strong midwestern derecho. In the Southwest we saw the start of another prolonged heat wave, which will be tomorrow’s main topic.

Also, we need to see some northwest flow aloft forming ahead of the system, which indeed took place on Monday. If the ridge is too strong, or warmer than what took place on Monday, a derecho won’t develop. In a warmer world, in which we are trending towards, more mid level “caps” where convection can’t form will take place, so derecho’s should trend farther north in summer and form earlier during the spring.

For many more details on yesterday’s fascinating but destructive derecho here is my friend, Matthew Capucci’s Washington Post article:

Destructive derecho brings 100 mph winds to Iowa, blasts through Chicago along 700-mile path

The storms struck the Midwest with the ferocity of a hurricane.

By Matthew Cappucci August 11, 2020 at 8:54 a.m. PDT

A vicious derecho, a fast-moving, violent thunderstorm complex, barreled through the Plains and the Midwest on Monday, bringing destructive winds along a 700-mile path that took it through the heart of Chicago. Wind gusts exceeding 100 mph ravaged Iowa, while there were confirmed tornadoes along the storms’ path, including one that swirled near the shore of Lake Michigan in Chicago’s Rogers Park neighborhood.

The violent windstorm killed one person in Indiana, and more than 1 million residents remained without power the morning after.

Along its path, fierce winds overturned trucks, flattened corn crops, and knocked trees onto homes and vehicles. Some structures were damaged in Iowa and northern Illinois. Social media images showed two-by-fours turned into projectiles puncturing the sides of buildings. In Wheaton, Ill., the excessive winds toppled a church steeple.

100-mph winds rake the Corn Belt

Derecho damage from Marshall County, Iowa, on Monday. (Marshall County Emergency Management)

The National Weather Service logged more than 700 reports of severe weather, including a wind gust to 112 mph in Midway, Iowa.

Marshalltown, a city 50 miles northeast of Des Moines in Marshall County, measured a wind gust to 99 mph. It had been struck by a violent tornado on July 19, 2018. The mayor described it as “deja vu all over again.” Elsewhere in the county, gusts ranged between 91 and 106 mph, akin to an enormous EF1 tornado.

The core of the most severe wind was at times 30 to 50 miles wide, with the swath of gusts locally exceeding 90 mph and lasting longer than 15 minutes in duration. In Marshalltown, the neighboring towns that trucked in aid in 2018 were unable to chip in after Monday’s blow, amid dealing with their own recovery.

Derecho damage from Marshall County, Iowa, on Monday. (Marshall County Emergency Management)

The Marshalltown Times-Republican reports that city police received more than 50 calls about possible gas leaks in the wake of the storms.

“This particular storm touched every corner of our community,” Mike Tupper, chief of police in Marshalltown, said in an interview. He said the town remains without power as crews grapple with the long task of cleanup.

“There’s a lot of significant rooftop damage to homes and businesses,” Tupper said. “Trees being taken down, a lot of poles taken down. The biggest challenge right now is with electricity.”

Tupper was struck by how long the winds lasted, which contributed to the damage. “These were sustained wind speeds well over 80 mph for 20-plus minutes,” he said.

In Ankeny, Iowa, a suburb on the northern side of Des Moines, city officials anticipate that the cleanup “could take up to four to six weeks to pick up the entire city,” according to a news release.

Derecho damage from Marshall County, Iowa, on Monday. (Marshall County Emergency Management)

The winds will probably result in enormous agricultural losses in Iowa, including to the corn crop, a staple of the Iowa economy. Corn is typically harvested between late September and mid-October, and at this time of year, it’s too late to replant.

Storms strike the Chicago metro area

In Chicago, winds gusted up to 73 mph as tornado sirens wailed throughout the city. A wind gust to 85 mph was recorded by a WeatherBug station in Lincoln Square, Chicago.

The storms cleared Monday evening while the setting sun cast delicate pastel hues across the evening sky, an odd contradiction of the fury that had ensued just a few hours earlier.

ABC7 News Chicago reported on the severity of damage to electrical lines in the area.

“It’s not just a repair job,” said Rich Negrin, a spokesperson for Commonwealth Edison, the largest electric utility in Illinois. “In some of the areas that are impacted, it’s actually a rebuild.”

Video emerged on social media of the winds peeling the roof off a building in downtown.

A brief tornado also touched down in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago, with an additional touchdown likely near Libson, southwest of the city.

Ahead of the storm, the National Weather Service warned Chicagoans of a “particularly dangerous situation” and advised they prepare for “tornado-like” winds.

Six injuries have been reported in the area served by the NWS Chicago, five being in Forreston, Ill., and one in Peru, Ill.

The Weather Service credited accurate forecasts and coordination with local officials for reducing the storm’s toll on the region.

“Despite the massive coverage and impressive intensity of the wind damage, there were a very limited number of serious injuries,” the Weather Service office serving Chicago wrote on its website. “This speaks to the effort of our partners including fellow meteorologists in the weather enterprise effectively communicating the threats and action needed to be taken, as well as emergency management and law enforcement for their preparedness efforts beforehand and assistance efforts immediately after.”

While there were no reports of significant winds greater than 80 mph in Indiana, one fatality did occur near Fort Wayne when a mobile home overturned in the high winds and trapped a pair of occupants. An adult woman was pronounced dead at a nearby hospital, while a boy escaped with minor injuries and was in “good condition.”

What is a derecho?

A time sequence of the derecho as it blasted eastward Monday. (NWS Chicago)

Derechos are arcing bands of thunderstorms that produce wind damage, some significant, along a path exceeding 400 miles. Monday’s was a “progressive” derecho, composed of one main bow echo — or curved squall line — containing a concentrated swath of wind.

What is a derecho? A meteorology professor explains these violent storms.

The wind was most extreme over Iowa and northern Illinois before storms fanned outward and brought slightly lesser winds to a much broader area.

The secret of derechos is their proclivity for tapping into jet stream energy. They form along the boundary of warm air to the south and cooler air to the north, feeding off the instability that results from the temperature contrast. Then warm, sinking air on the back side of the storms dries up and helps drag down strong jet stream momentum. This “rear inflow jet” is what nudges the center of the squall line forward and causes the storms to “bow out.”

A 700-mile path of fury

Monday’s derecho actually developed from the same weather pattern that produced storms with softball-sized hail over the Black Hills west of Rapid City, S.D., on Saturday. More storms affected Minneapolis on Sunday.

By early Monday morning, fledgling storms over South Dakota had dipped into Nebraska, causing power outages to start the day in the greater Omaha area.

But as they moved into Iowa, the storms began taking on the classic “bow echo” shape — aptly named for their archer’s bow-like appearance. Shortly thereafter, Doppler radar detected winds of 120 mph at just 1,800 feet elevation — a sign that wind gusts over 90 mph were possible in the northern Des Moines suburbs.

Storm reports from Monday’s derecho. (NOAA/SPC)

Wind velocities that strong are more typically only spotted on radar associated with intense tornadoes or landfalling hurricanes.

At their peak, the storms were producing upward of 70 to 100 cloud to ground lightning flashes per minute.

The storms became outflow dominant as they approached Chicago, meaning they were exhaling more air than they were ingesting as the rapidly-moving squall started to outrun its upper-level support. In the process, several kinks in the line developed, where surges of air exiting the storm contributed to localized zones of spin. That prompted several tornado warnings for parts of Chicago.

The force of the winds, coupled with the change in air pressure accompanying them, even raised concerns of a “meteotsunami” affecting eastern Lake Michigan. The National Weather Service in Northern Indiana issued a lakeshore flood warning to account for oscillations in water levels resulting from the storms’ passage. Data suggests a 1 to 2 foot swing occurred.

“Fluctuating water levels will continue in the wake of Monday evening storms,” wrote the National Weather Service. “This will cause an increased risk for dangerous RIP currents and structural currents as well as lake shore flooding through [Tuesday] morning.”

Winds remained strong in Chicago even after the leading edge of storms passed, with some locations reporting 20 to 30 minutes of winds gusting above 50 mph. That was the result of a “wake low,” or a low pressure system formed by subsiding warm, dry air on the back side of the storms.

It’s been a busy season for derechos, which have caused problems from the High Plains to the East Coast.

Philadelphia was hit by a progressive derecho with 80 mph winds on June 4. Gusts topped 90 mph east of the city in New Jersey.

A deadly derecho slammed Nashville with 70-mph winds, snapping trees and knocking out power

Two days later, western parts of the Dakotas were blasted by strong derecho winds and a few tornadoes.

Earlier this year, a derecho brought 70 mph wind gusts to Nashville in May.

Jason Samenow and Andrew Freedman contributed to this article.

Matthew Cappucci is a meteorologist for Capital Weather Gang. He earned a B.A. in atmospheric sciences from Harvard University in 2019, and has contributed to The Washington Post since he was 18. He is an avid storm chaser and adventurer, and covers all types of weather, climate science, and astronomy. Follow

Here is more climate and weather news from Tuesday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)

Here is an “ET” from Tuesday:

Now here are some of today’s articles and notes on the horrid COVID-19 pandemic:

(If you like these posts and my work please contribute via the PayPal widget, which has recently been added to this site. Thanks in advance for any support.)

Guy Walton “The Climate Guy”