Antarctic Sea Ice- Another Troubling Trend

Sunday January 20th… Dear Diary. The main purpose of this ongoing post will be to track United States extreme or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials)

Segueing off of yesterday’s post on permafrost it came to my attention last week that Antarctic see ice has declined to record low levels in early 2019 in conjunction with what has become a torrid summer in the Southern Hemisphere.

Also last year I posted on how high globally averaged temperatures would need to rise above preindustrial conditions in order for Antarctic Ice to become a tipping point, bringing additional warmth into Earth’s climate system: https://guyonclimate.com/2018/08/23/extreme-temperature-diary-august-22-2018-topic-tipping-point-discussionpart-13-antarctic-ice/

Last week’s news in association with the Antarctic is troublesome.

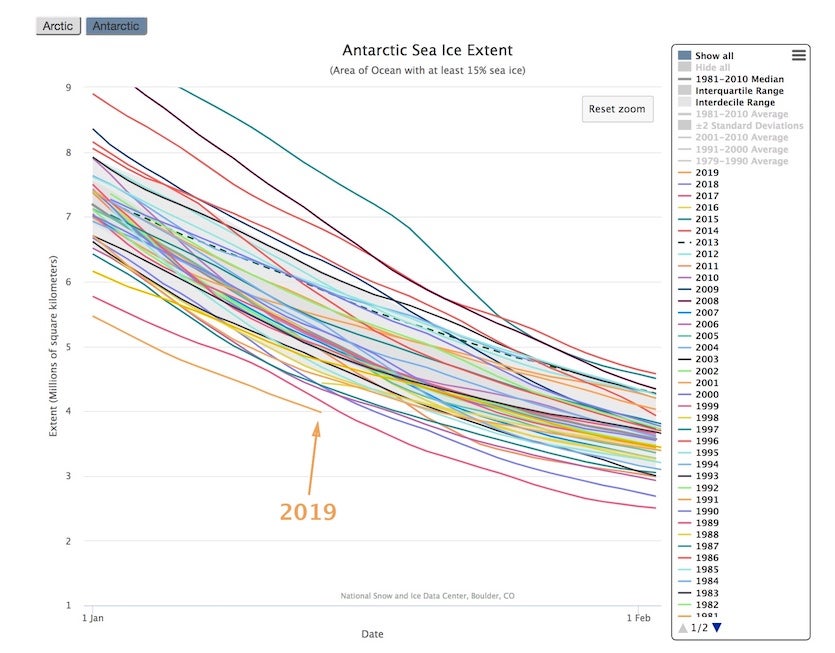

I’ve posted several times this season on Australia’s record heat from December and early January. The one chart we will concentrate on today should give everybody pause and is another clear warning that climate change isn’t some nebulous, futuristic change that our grandkids will have to deal with. It is happening now:

Figure 1. Antarctic sea ice extent has been running well below all other years during the first two weeks of January 2019. Image credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center.

This chart is from Bob Henson’s Category 6 Blog dated 1/16/2018. I would invite all to read this in it’s entirety:

https://www.wunderground.com/cat6/Antarctic-Sea-Ice-Dips-Record-Low-Extent-Early-January

What I will do today is repost material in association with this startling ice chart:

Just two years after shrinking to its lowest extent ever measured, Antarctic sea ice may challenge that record a few weeks from now. This depletion comes just as scientists reported a harrowing sixfold increase in the loss of Antarctic land ice over the last 40 years. Unlike land ice, the loss of sea ice doesn’t contribute to sea level rise in itself, but it could help make some of Antarctica’s land ice more vulnerable (see below).

The extent of ice cover encircling the Antarctic coast began taking a nosedive in December, dropping even more quickly than usual for the time of year (late spring in the Southern Hemisphere). Since December 25, Antarctic ice extent has set calendar-day record lows every day for more than three solid weeks. Satellite-based records from the National Snow and Ice Data Center go back to 1979.

Typically, Antarctic ice reaches its minimum for the year in late February or early March (late summer). As of Monday, January 14, the extent was 3.979 million sq km, which is well below the value of 4.154 million sq km observed on that date in 2017. We still have a few weeks to go before 2019’s extent can challenge the lowest value measured at any time of year: 2.110 million square kilometers, observed on March 3, 2017.

A new all-time record-low extent isn’t yet a slam dunk, according to polar climate expert Cecilia Bitz (University of Washington). “The minimum won’t happen for another 40 days or so, and the weather between now and the minimum could shrink or grow the margin that exists today,” Bitz said in an email.

Antarctic sea ice actually become slightly more extensive, about 1-2% per decade, from the 1970s into the early 2010s, a development that’s not yet fully understood. A majority of simulations carried out in support of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report predicted that Antarctic sea ice coverage should have declined between 1979 and 2013. The actual observed increase wasn’t hugely significant, but it did lead to successive record-high extents in 2012, 2013, and 2014.

In a 2015 review paper published in Nature Climate Change, a group of Antarctic experts identified some factors that may have enhanced regional sea ice production in spite of global warming. These included:

—stronger westerly winds ringing the continent

—increased meltwater flowing into the Southern Ocean

—a stronger prevailing low in the Amundsen Sea. This tends to favor cold offshore flow and enhanced ice production in the Ross Sea, with mild onshore flow and reduced sea ice in the Amundsen-Bellinghausen region.

Whatever its causes, the unexpectedly resilient Antarctic sea ice certainly wasn’t enough to make up for the myriad effects of planetary warming elsewhere. As Jeff Masters once put it: “Calling attention to Antarctic sea ice gain is like telling someone to ignore the fire smoldering in the attic, and instead go appreciate the coolness of the basement, because there is no fire there.”

A dramatic about-face

Years of extra-abundant Antarctic sea ice came to a halt in mid-2015, when ice extent began dropping below average. The melt season of 2016-17 brought even more dramatic losses, including the record low extent noted above. The sea ice was only slightly more abundant in 2017-18.

“We’ve always suspected that the expansion of Antarctic sea ice which occurred through 2014 or so was a trend destined to reverse itself in a warming climate,” David Schneider (National Center for Atmospheric Research) said in an email.

The record-low ice extent of 2015-16 was produced by that year’s record-strong El Niño together with natural variability, according to a 2016 paper in Geophysical Research Letters led by UW’s Malte Stuecker, a postdoctoral researcher working with Bitz. They found that the powerhouse El Niño helped boost sea surface temperatures in the eastern Ross, Amundsen, and Bellinghausen Seas. Similarly, it’s possible that warmth across the tropical Pacific—though now short of a full-fledged El Niño—may also be helping to warm the southern seas.

“El Niño is associated with atmospheric circulation patterns that raise sea surface temperatures and limit the expansion of sea ice around Antarctica,” said Schneider. There’s also longer-term warming of the Southern Ocean waters, which could be starting to have more of an effect on sea ice as well. “It will take focused study, careful observations, and computer modeling to really solve the puzzle,” Schneider said.

Researchers are also casting their eyes on the potential impact of Antarctic ice loss on a matter of intense interest: the ice shelves that keep massive volumes of ice from flowing seaward and pushing sea level to catastrophic heights. Robert Massom (Australian Antarctic Division) and colleagues examined this topic in a 2018 paper in Nature, “Antarctic ice shelf disintegration triggered by sea ice loss and ocean swell.” Their modeling showed that the much-publicized collapses of the Larsen A and B and Wilkins ice shelves may have been hastened by longer periods of ice-free conditions that allowed waves to batter and destabilize the shelves.

“Our analysis of satellite and ocean-wave data and modelling of combined ice shelf, sea ice and wave properties highlights the need for ice sheet models to account for sea ice and ocean waves,” Massom and coauthors concluded.

Obviously the less surrounding sea ice around Antarctica the lower the albedo due to darker waters; thus, the more vulnerable land ice that if melted could lead to sea level rise by many feet with time.

For those of you in the Northern Hemisphere enjoy the cold weather and snow the next couple of months. I have a funny feeling that you will surely miss it once it is our turn to experience summer.

……………………………………………………………………………………………

Here is some more weather and climate news from Sunday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity.)

Here are some of today’s chilly “ETs:”

(If you like these posts and my work please contribute via the PayPal widget, which has recently been added to this site. Thanks in advance for any support.)

The Climate Guy