The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track global extreme or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😉

Main Topic: New California Wildfire Attribution Study Confirms Climate Change as a Culprit

Dear Diary. When the California fires were consuming the Palisades and other neighborhoods around Los Angeles easier this month, I quickly put the blame on climate change because large scale winter wildfires are highly out of season in California:

Only a few weeks later we have a scientific verdict coming from a quick turnaround attribution study indicating that the fires were made 35% worse because of climate change, confirming my charges.

Here is a thorough report from Dr. Jeff Masters:

Climate change made deadly Los Angeles wildfires 35% more likely: new attribution study

The fires, likely to be the costliest in world history, were made about 35% more likely due to the 1.3°C of global warming that has occurred since preindustrial times.

by Jeff Masters January 28, 2025

A firefighting helicopter drops water as the Sunset Fire burns in the Hollywood Hills with evacuations ordered on January 8, 2025 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Human-caused climate change worsened the ferocious January 2025 Los Angeles wildfires by reducing rainfall, drying out vegetation, and increasing the overlap between fire season and the winter Santa Ana wind season, according to a rapid analysis released today by World Weather Attribution, conducted by 32 researchers, including leading wildfire scientists from the U.S. and Europe. The fires burned over 50,000 acres, killed at least 28 people, and destroyed over 16,000 structures, according to Cal Fire. The study’s main findings:

- The hot, dry and windy conditions that drove the fires were about 35% more likely and 6% more intense due to 1.3 degrees Celsius of global warming that has occurred since preindustrial times, caused primarily by the burning of oil, gas and coal.

- These fire-prone conditions can be expected to recur about once every 17 years in the current climate, but will become a further 35% more likely if warming reaches 2.6 degrees Celsius by 2100, which is predicted to happen under three of the five main IPCC emission scenarios (from moderate to high-end).

- Low rainfall from October through December in the current climate is about 2.4 times more likely compared to the preindustrial climate, but this change cannot be confidently attributed to human-caused climate change.

- Fire-prone conditions because of human-caused climate change have increased by about 23 extra days each year, increasing the chance a fire will start from October through December, which coincides with the onset of peak Santa Ana wind season.

- Water infrastructure, not designed to fight a rapidly expanding wildfire, was unable to keep up with scale and extreme needs during the Eaton and Palisades wildfires.

The results echo the conclusions of an earlier UCLA rapid attribution study, which found, “Climate change may be linked to roughly a quarter of the extreme fuel moisture deficit when the fires began. The fires would still have been extreme without climate change, but probably somewhat smaller and less intense.”

How the stage was set for the wildfires

The rainy season in California usually begins between October and December, and typically marks the end of the wildfire season, nullifying the ability of the powerful wintertime Santa Ana winds to easily spread large and intense fires. However, Los Angeles County received its lowest May-December precipitation on record in 2024 (0.31 inches, 4.6 inches below average), accompanied by its fifth-hottest May-December temperatures on record, meaning that grasses and brush were dry and highly flammable when the fires broke out. (A primary way in which climate change worsens wildfire is through a strong, warming-driven increase of the atmosphere’s “thirstiness” or vapor pressure deficit, which exerts a drying effect on vegetation.) Additionally, above-average precipitation in the winters of 2022/23 and 2023/24, plus the record rains from Hurricane Hilary in the summer of 2023, had previously encouraged vegetation growth, providing more fuel for the fires (wildfires in this ecosystem are often limited by the amount of fuel they have).

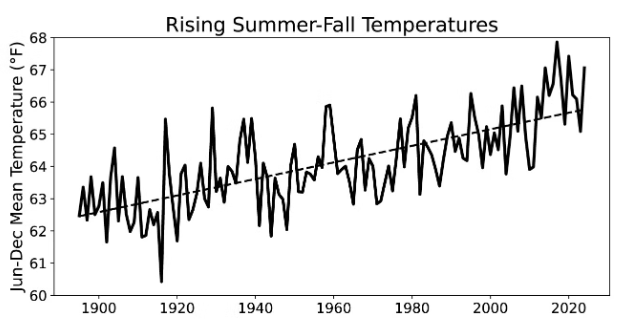

Figure 1. Annual mean summer-fall (June through December) temperatures averaged over coastal Southern California for the period of 1895-2024. Data are from PRISM, via the 2025 UCLA Los Angeles wildfire attribution study.

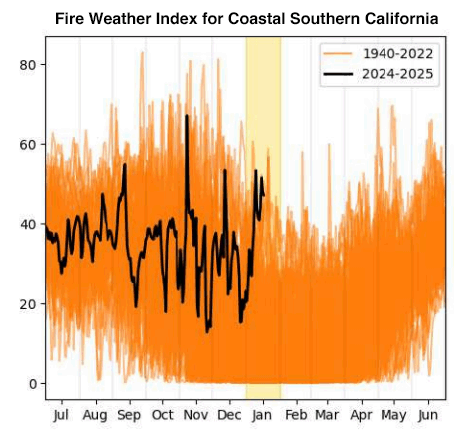

To evaluate how wildfire risk is changing, the study looked at four measures: a drought index (using measured rainfall from October through December), the Fire Weather Index (FWI), which uses meteorological information (temperature, humidity, wind speed, and precipitation over the preceding weeks and days), the timing of the end of the dry season, and how circulation pattern that create the Santa Ana winds are changing. Their findings:

- The observed drop in precipitation (i.e., meteorological drought) was about a 1-in-20-year event in the current climate but would have been a 1-in-49-year event in the preindustrial climate (2.4 times less likely). However, climate models do not agree on the direction of precipitation trends in this region, and “we are unable to formally attribute this change to global warming,” the researchers concluded.

- Looking beyond precipitation alone, eight of the eleven models examined showed an increase in extreme January values of the Fire Weather Index (FWI) in Southern California, “increasing our confidence that climate change is driving this trend”, the authors wrote. They added, “Combining models and observations, we find that human-induced warming from burning fossil fuels made the peak January FWI more intense, with an estimated 6% increase in intensity, and 35% more probable.”

- Analyzing observations, the study found that “the length of the dry season has increased by about 23 days since the [period when] global climate was 1.3°C cooler. This means that, due to the burning of fossil fuels, the dry season, when a lot of fuel is available, and the Santa Ana winds, that are crucial for the initial spread of wildfires, are increasingly overlapping.” They attributed this increase in the dry season length to human-caused global warming.

- Analyzing observations, the authors found that “the frequency of an atmospheric circulation pattern such as that of January 8, 2025, which is known to strengthen Santa Ana wind events, has increased in winter, raising the risk of weather conditions that drive the spread of wildfire. Whether this trend is attributable to human-caused climate change requires a more in-depth study of the patterns in observations and climate models.” For the future, climate models predict that global warming may promote a slight reduction in the frequency of early season (mainly Sep.-Nov.) Santa Ana winds because of a decreasing cool-season temperature differential between the ocean and continental interior, but this has not yet been observed. Little change in the magnitude of the strongest Santa Ana wind events is anticipated from future climate change.

The study did not look at how the enhanced vegetation and fuel loads caused by the extra precipitation that fell during the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 wet seasons may have been influenced by climate change. However, the UCLA attribution study found that a small part (~10%) of this excess precipitation could be attributed to climate change. They wrote: “This effect may be associated with climate “whiplash”, a phenomenon where climate change is simultaneously projected to intensify precipitation totals in wet years, but also to intensify drought in dry years (Swain et al. 2018, Swain et al. 2025)”.

Figure 2. Daily Fire Weather Index (FWI) based on ERA5 data in 2024/2025 (black) compared to recent years since 1991 (orange). January is highlighted in yellow. Record daily highs were observed during a portion of January 2025. (Image credit: Weather Attribution group)

Costliest wildfire in world history

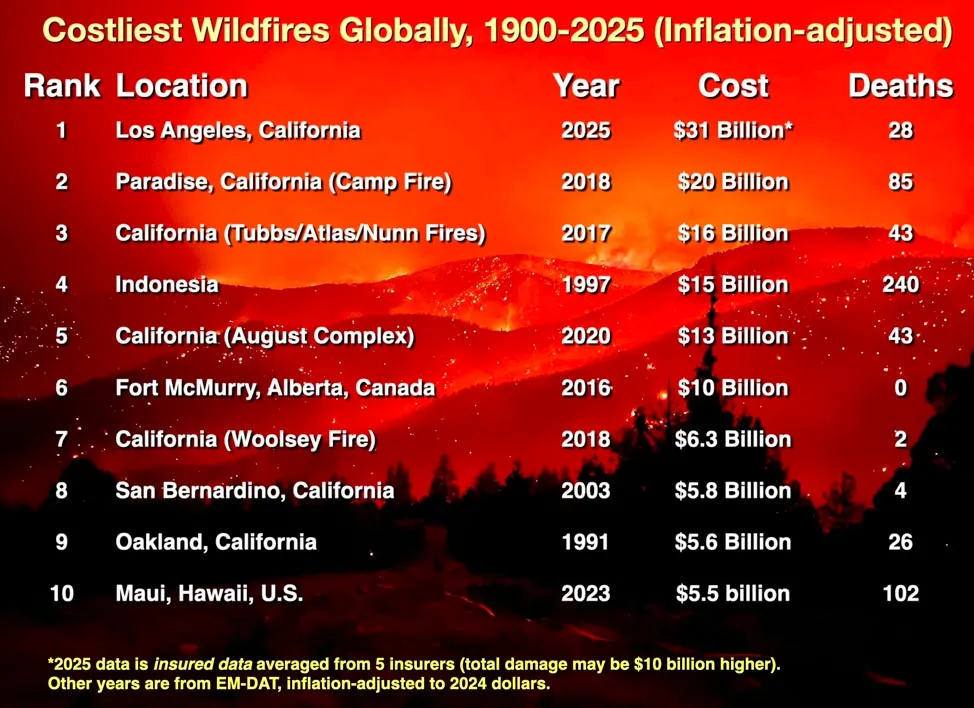

There is little doubt that the two January 2025 Los Angeles wildfires, the Palisades Fire and the Eaton Fire, will collectively be the costliest wildfire event in world history, even after adjusting previous events for inflation. A Jan. 23 analysis of insured damage estimates of the fires from insurance brokers Gallagher Re, Moody’s RMS, CoreLogic, Karen Clark & Company, and Verisk averaged $31 billion. Total damages will be much higher; Goldman Sachs estimated that total damages could be $10 billion higher, and one expert I heard from told me, “the direct overall economic cost will be as much as double the insured loss, but we won’t have clarity on that for a while. This is a rather complex situation on the insurance side.” (Note that damage estimates from weather company AccuWeather, of up to $250 billion, are not included, since their disaster damage estimates are typically wildly inflated from industry standard practices.)

Figure 3. Costliest wildfires in world history, according to inflation-adjusted numbers from EM-DAT. Preliminary insured damages for the 2025 Los Angeles fires are included (uninsured damages for these fires are not included).

According to Verisk, insured losses for the Palisades fire will be $20-25 billion, and will be $8-10 billion for the Eaton fire. Using inflation-adjusted damage estimates from EM-DAT, the international disaster database, the 2025 Palisades Fire alone would be the costliest fire in world history (Fig. 3). The previous record was held by the catastrophic Camp Fire of 2018, which killed 85 people in Paradise, Calif., and cost $20 billion. The 2025 Eaton Fire would likely rank as the sixth-costliest fire in world history.

By number of structures destroyed, the Palisades and Eaton wildfires are the second and third most destructive wildfires in California, trailing only the Camp Fire of 2018.

Welcome rains fall in Los Angeles, but bring mudslides

The first significant precipitation since May fell in Southern California on Sunday and Monday, bringing widespread rains of 0.5-1.5 inches to fire-ravaged areas and snow to the higher peaks. In Los Angeles, 0.61 inches of rain fell on Sunday – more precipitation than fell in the previous eight months combined. These welcome rains should significantly reduce the fire danger in the coming weeks. Thanks in part to the rains, the Palisades and Eaton wildfires are now both more than 95% contained.

Heavy rains falling on recently burned slopes are a recipe for destructive mudslides and debris flows. On Sunday, mudslides closed portions of the Pacific Coast Highway, Palisades Road, and Topanga Canyon Boulevard, which were affected by the Palisades Fire (see Twitter post below). Fortunately, these debris flows were not widespread or particularly damaging.

The forecast: dry

The forecast for the coming two weeks, unfortunately, is dry, and it is possible that this past weekend’s storm will end up being the largest precipitation event of the entire winter for Los Angeles. The Tuesday morning runs of the GFS and European models are predicting no significant precipitation for Southern California for at least the next week, with total rainfall amounts less than .05 inches (1 mm) – though some wet weather on Feb. 6 is being advertised as a possibility. Without more precipitation, fire risk will re-emerge in 10-14 days if the Santa Ana winds return, according to climate scientist Daniel Swain. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Ryan Kittell, a National Weather Service meteorologist in Southern California, said that about 2-4 inches of rain are needed to end the fire season.

In the longer term, La Niña conditions have become entrenched over the Eastern Pacific, and this pattern tends to shift the jet stream farther northward, bringing below-average precipitation to Southern California and above-average precipitation to Central and Northern California. Indeed, that is the forecast through mid-March from the latest 46-day run of the long-range European model ensemble (see Tweet below). If this forecast verifies, summer will likely bring extreme wildfire risk to Southern California.

Bob Henson contributed to this post.

more like this

Storm Eowyn brings hurricane-level destruction to Ireland

The planet had 58 billion-dollar weather disasters in 2024, the second-highest on record

A high-impact week, from a snowy Gulf Coast to shrieking California winds

Dr. Jeff Master’s Climate Change Made Deadly Los Angeles Wildfires 35% More Likely: New Attribution Study was first published on Yale Climate Connections, a program of the Yale School of the Environment, available at: http://yaleclimateconnections.org. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 license (CC BY-NC-ND 2.5).

Related:

Here are more “ETs” recorded from around the planet the last couple of days, their consequences, and some extreme temperature outlooks, as well as any extreme precipitation reports:

Here is More Climate News from Wednesday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)