The main purpose of this ongoing blog will be to track planetary extreme, or record temperatures related to climate change. Any reports I see of ETs will be listed below the main topic of the day. I’ll refer to extreme or record temperatures as ETs (not extraterrestrials).😜

Main Topic: Consequences of the Great Salt Lake Drying Up

Dear Diary. If you want proof that the southwestern U.S. has been experiencing a very long-term drought, look at what has been happening to Utah’s Great Salt Lake. This large expanse of water may totally dry up later this century should the historic drought continue.

Obviously, the receding shoreline of the lake spells unwanted consequences for those living in the vicinity of the Great Salt Lake. Occasional winds whipping around area lift salt into the air making life miserable for residents, for example.

Here are more details from the Washington Post:

As the Great Salt Lake dries up, clouds of dangerous dust blow into boomtowns – The Washington Post

As the Great Salt Lake dries up, clouds of dangerous dust blow into boomtowns

Dozens of dust events probably happen each year across the 120-square-mile playa once covered by the Great Salt Lake. But there are no comprehensive state or federal records of them.

8/17/2024 at 6:00 a.m. EDT

By Ruby Mellen and James Roh

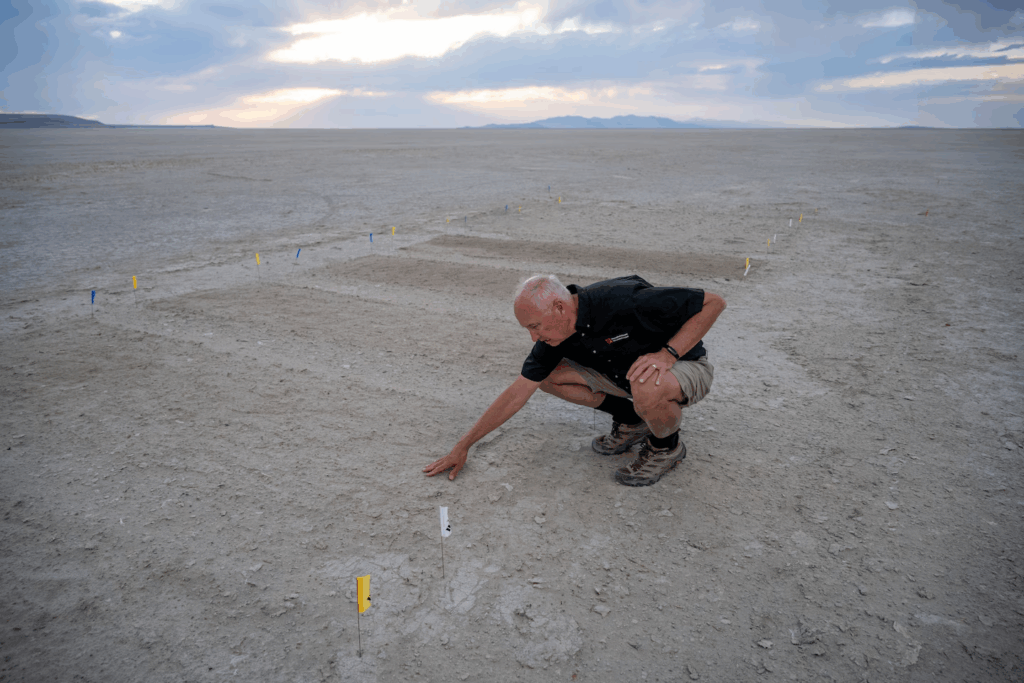

GREAT SALT LAKE, Utah — Kevin Perry was standing on the parched lakebed when the wind started to pick up.

He squinted across a cracked, gray expanse of earth, submerged 16 feet underwater just five decades ago, and saw a wall of dust headed straight for him.

The sand-like specks — probably laced with arsenic and other carcinogenic metals — stung his bare arms and legs as the gusts intensified. After several minutes of deafening squalls and blinding grime, the wind stilled, but the cloud kept barreling toward the shore.

“And it’s rolling into all those neighborhoods,” said Perry, gazing at dozens of homes that have cropped up near what was once the shore of one of the West’s most famous landmarks.

“The question is, how much of it?”

Kevin Perry, professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Utah, examines a dust mitigation test site on the exposed lakebed of Farmington Bay, which is part of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. (James Roh/For The Washington Post)

Dust blows across Farmington Bay. (James Roh/For The Washington Post)

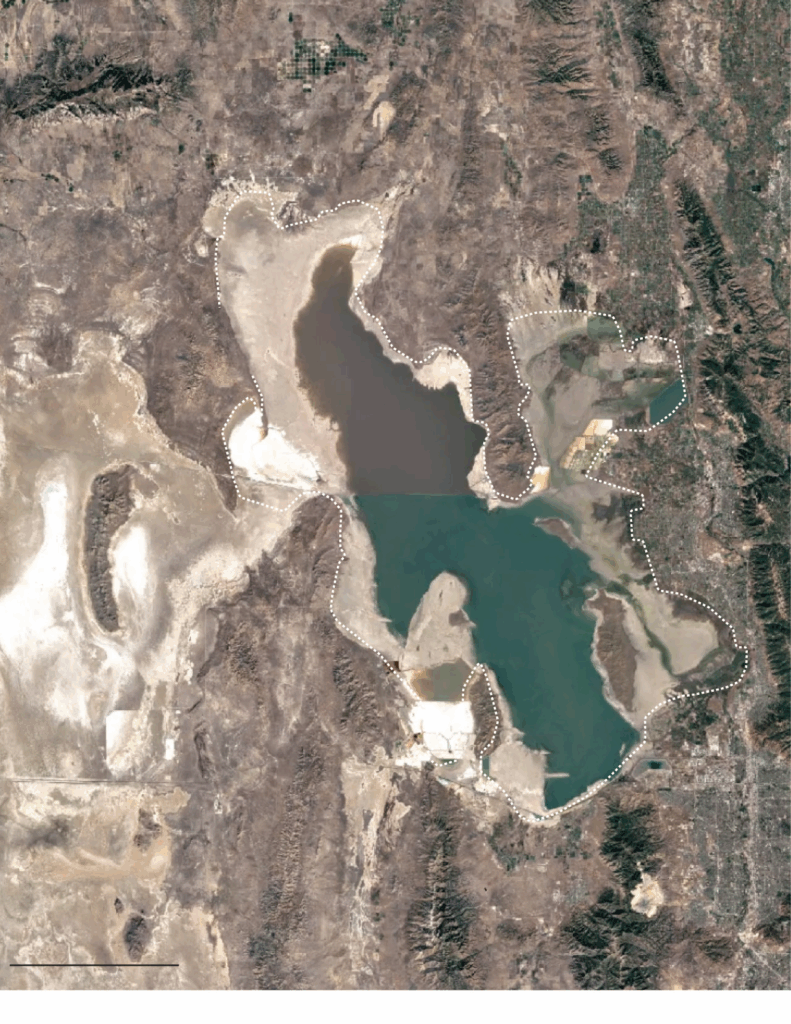

Dozens of dust events like this, carrying harmful heavy metals and chemicals, probably happen each year across the 120-square-mile playa once covered by the Great Salt Lake, before water diversions, drought and heat caused it to shrink to record lows. But there are no comprehensive state or federal records of them — no centralized method for tracking and understanding the long-term effects they are having on Utah’s ballooning population.

Source: Google Earth, 2022

What scientists do know is that the dust is full of hazardous chemicals. Sampled from the lakebed, levels surpass federal recommendations for what you should be exposed to in your home and are more concentrated than those from other dust hot spots in Utah, said Perry, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Utah.

But the recent discoveries haven’t deterred many people from moving to a part of the country that boasts access to national parks, world-class skiing and an emerging tech sector dubbed the “Silicon Slopes.” Utah was the fastest-growing state in the country in 2020 and was in the top five in 2024.

“It’s really hard for people to perceive the risk,” said Jesse Keenan, an associate professor of sustainable real estate and urban planning at Tulane University. “It’s not so viscerally violent.”

Widespread alarm over this lake emerged about three years ago, when its water levels hit a record low. The state legislature passed several laws aimed at conserving water, and the majority of Utahns say they want to save the lake. But scientists said the laws have done little to address growing risks from the dust itself and the lack of monitoring, leaving millions of residents caught in the headwinds of environmental uncertainty.

Agriculture and family homes populate Scarsdale, Utah, a town bordering a dried playa of the Great Salt Lake. (Video: James Roh)

‘We’ve done this experiment before’

The Great Salt Lake descended from Lake Bonneville, a prehistoric body of water formed around 32,000 years ago. It was about 1,000 feet deep in some parts and roughly the size of West Virginia. After the Ice Age, as the planet warmed, Bonneville evaporated, forming several lakes in the Great Basin, including Great Salt Lake, some 11,000 years ago.

Great Salt Lake has no outlet. Its levels depend on how much water flows into it from rivers and streams in the surrounding mountains, and how much water evaporates out of it. Since the federal government began tracking its depth in the 1840s, it has always fluctuated. But since the 1980s, the elevation has been declining at a higher rate than normal.

Wading near the shore of Antelope Island, Great Salt Lake Institute coordinator Georgie Corkery, left, and Westminster student Kimber Jeffrey collect samples of organisms that grow in the lake to better understand how life is adapting to the rapid changes. (James Roh/For The Washington Post)

Several factors play a role, said Bonnie Baxter, director of the Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster University. More people have moved to the area, using water for industry, farming and construction. At the same time, increased temperatures linked to human-driven climate change have caused the lake to lose nearly three feet of water each summer. Add to the equation the worst prolonged drought the Southwest has seen in 1,200 years, and you’ve got miles of exposed lakebed containing concentrated chemicals once diluted by water. Now they blow into decade-old subdevelopments that boast luxurious names such as Still Water Lake Estates and Simpson Springs.

The last two years saw above-normal snowfall for the lake’s surrounding mountains, bringing water levels up. The increase was the “single worst thing that ever happened to the lake,” Baxter said. “Because it brought complacency.” Now the lake is poised to return to a state of decline.

It’s not clear what the dust could do to people nearby, but past examples portend a sinister prognosis.

“We’ve done this experiment before,” Baxter said.

Saline bodies of water around the world are shrinking, due to conditions similar to those in Utah. The Aral Sea in Central Asia — once the world’s fourth-largest lake — has lost around 90 percent of its volume since water was diverted for crops starting in the 1960s. Studies have linked its dust emissions to reduced kidney function in children living nearby. Iran’s Lake Urmia dropped more than 23 feet in two decades, significantly contributing to health problems in nearby neighborhoods.

Baxter fears how the lake’s drying will affect an expanding area of more than 2 million people.

Northern Utah’s Wasatch Front, home to nearly 90 percent of the state’s population, has seen tens of thousands of new residents annually in recent years. The region’s most populous hub, Salt Lake City, is also one of its fastest growing — it has been redeveloping a 100-acre site on its west side called the Power District, whose plans include a new Major League Baseball stadium. It’s also preparing to host the Winter Olympics in 2034.

“It’s so scary, it really is,” Baxter said. She gets calls several times a week from people asking whether it is safe to stay in the area. It’s a conversation she’s had with her family. But her work studying the lake’s ecosystem keeps her rooted for now.

Diverted tributaries and historic drought has left roughly 800 square miles of the Great Salt Lake lakebed exposed. (Video: James Roh)

Hazy forecasts

Lake dust is a huge concern for the seven members of the Parker family, five of whom are asthmatic.

Their home in the foothills of Salt Lake City, purchased a year ago, has sprawling views of the valley below and the dust wafting off the lakebed. Beth Parker is in the midst of renovations, tearing out the wall-to-wall carpet and replacing the curtains that she calls “dust collectors.” She’s adding a mudroom to keep people from tracking in outside particles.

Her daughter Katherine, 15, rows crew on the lake in the spring and fall. If the air looks especially bad, she’ll make sure to bring her inhaler.

“The dust feels different,” she said, sitting in the family’s living room. “It makes it harder to breathe, more so than pollution.”

On a text chain, parents discuss whether it’s too hazy to hold soccer practice, said Wells, Katherine’s father. Since 2022, when the lake was at an all-time low, he said practice has been canceled more frequently. It’s hard to know for sure when it’s safe to be outdoors.

“Without proper monitoring, we don’t know which precautions we should take,” said Beth, an environmental law professor at the University of Utah who is working on lake-related issues. “If the lake continues to decline, the livability of the region is on the line,” she added.

The counties near the lake have six federally regulated air quality monitors that track lake dust. The monitors don’t routinely look at the composition of the dust.

“We don’t have the broader network that allows us to answer the question of when there are dust storms, what’s in that dust and who might be affected,” said Tim Davis, executive director of the Utah Department of Environmental Quality. By contrast, Owens Lake, a receding saline lake in California, has at least nine monitors. It’s more than 10 times smaller than the Great Salt Lake.

Bison forage for food on a historically submerged section of Farmington Bay in Utah’s Great Salt Lake. (James Roh/For The Washington Post)

Davis is trying to fill the gap. He has funding to hire an air quality expert who will specialize in lake dust. He’s also hoping to install 19 other air quality monitors around the state that will include filters that can trap dust for analysis. The move has come under criticism from scientists, including Perry, because the monitors won’t be run in accordance with federal standards — which means if they detect hazardous levels, the state wouldn’t be compelled by the Environmental Protection Agency to address them. Davis said he’s running the monitors in a way they can gather the most information.

“The bigger network we’re building will be more flexible,” he said. “It will allow us to get data from places that aren’t where we would normally put a regulatory monitor.”

While the EPA said it has no plans to monitor the lake dust on a federal level, Marisa Lubeck, an agency spokesperson, added that it “supports Utah’s leadership in actively monitoring and conducting research to understand dust from the Great Salt Lake and its potential impacts.”

Even in places where monitoring is in place, there’s fear that conditions will deteriorate further if the lake keeps receding.

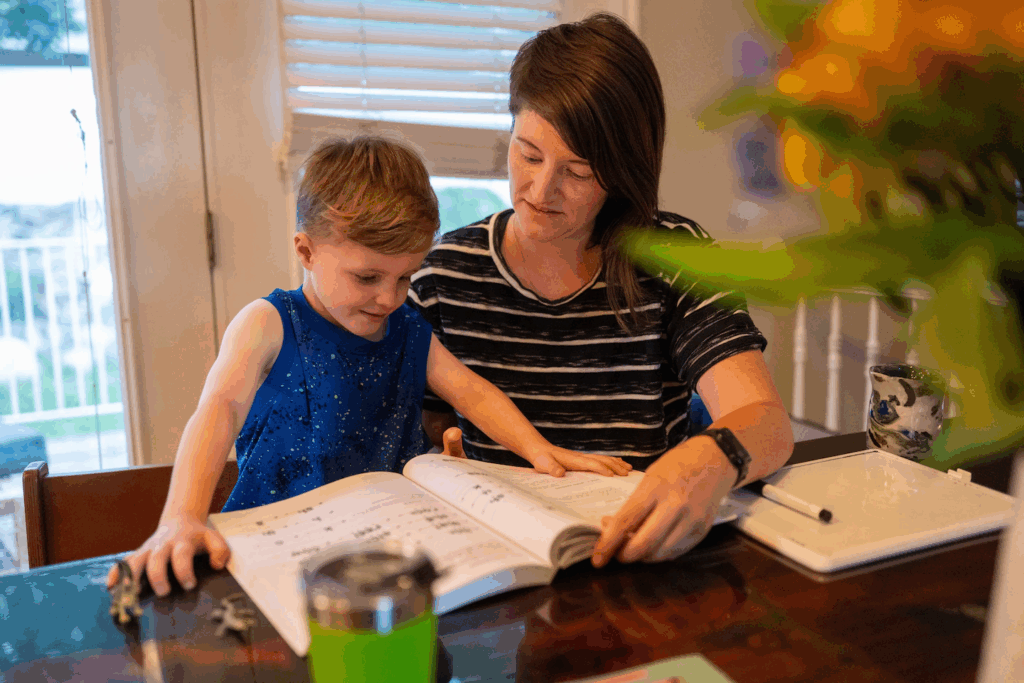

The haze hung heavy on a Wednesday morning in Ogden, a hub north of Salt Lake City, as Kellie Bornhoft and her son Felix settled in for their post-breakfast reading lesson. The 4-year-old was put through his paces, sounding out “spider” and “kite” until he paused, stumped.

“This is mommy’s favorite thing,” Kellie gently urged.

“A rock,” Felix slowly sounded out.

Kellie Bornhoft, right, practices reading exercises with her son Felix at their home in Ogden, which is about 10 miles east of Great Salt Lake. (James Roh/For The Washington Post)

Bornhoft shows off her artwork in her studio at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art. Bornhoft is an artist who has concerns about the health consequences of living near the drying Great Salt Lake. (James Roh/For The Washington Post)

Kellie, an artist in residence at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, creates works that examine people’s relationship with climate change. She immediately became fascinated with the lake. Her latest installation looks at what she calls “dirty diamonds”: cloudy crystals that emerge from places on the lakebed where water used to be.

“They’re artifacts of loss,” Kellie said.

The family moved to Utah from the Bay Area in 2023 for her job, and they just bought a house, despite being hyperaware of the dust and potential outcomes.

“This is one environmental crisis of many,” said Kellie, seated on her living room floor and scratching her husky, Onyx, behind his ears. When they moved from California, they had experienced catastrophic fires near them. Blazes farther away turned the sky above a deep orange. “You can make the choice to run from it, or stay and try to fix it.”

Not everyone sees the dust as a severe issue. Chris Sloan and his wife Berna work as real estate agents in Tooele, in one of the fastest-growing counties in the state, just south of the lake. Prices and demand have skyrocketed in the area in the last decade, they said, and their clients have never expressed concern about the nearby lakebed.

“The dust generally doesn’t come our way,” said Chris, as he navigated his wife’s silver Audi through developments off Interstate 80, which traverses the lake’s hazy southern shoreline.

In April, Grow the Flow, a nonprofit committed to protecting the lake, recorded a dust storm that swept through counties including Tooele but went unrecorded by state monitoring.

“We’re staring down the barrel of the biggest public health crisis our state has ever seen,” said Ben Abbott, the organization’s executive director. “And [people] just don’t know.”

But to Chris, the April event was “just another day in Tooele County.”

“It’s breezy here, and there’s lakebed,” he said.

Dust containing harmful heavy metals and chemicals sits on top the Great Salt Lake’s exposed bed. (Video: James Roh)

A new experiment

This summer, after nearly a decade of sampling and studying the dust, Perry, the atmospheric scientist, embarked on a new research initiative to try to keep it from blowing.

As evening settled over the valley, easing the searing July heat, he mounted a thick-tired bike and pedaled some two miles out on the playa, to a remote research station. The thin weather tower collects data on rainfall, wind speed and particle measurements. The dust event that swept through during his ride out peaked at over 3,000 micrograms per cubic meter, Perry said, about 20 times greater than the federal standard for 24 hours.

Perry bikes to a test site where he is performing dust mitigation tests on the exposed lakebed of Farmington Bay. (James Roh/For The Washington Post)

Next to the station is a square of earth, methodically divided into several sections. Perry mists the portions of dirt with different kinds of solutions — fresh water, salt water and water from nearby rivers — to see which forms the strongest and longest-lasting crust. With a thick overlay, not as much dust would blow into populated areas.

It’s an early experiment, and he’s unsure how it could be scaled to cover the dozens of miles of exposed dirt. Ultimately the better solution, he said, is the simpler one: to shepherd more water to the lake.

“I want all of my research to be underwater in 20 years,” Perry said. “I want people to forget that I ever did it.”

He’s ridden his trusty blue bike a total of over 2,700 miles across the playa to take samples, discovering shipwrecks, animal carcasses, car parts and century-old “kidney tonics” along the way.

A full moon rose over the playa, its reflection glinting off the skyscrapers of Salt Lake City in the distance.

Perry took a long gulp of water and swung a leg over his bike — there was more data to collect.

By Ruby Mellen Ruby Mellen reports on climate change and the environment for the Washington Post. follow on Xrubymellen

Here are more “ET’s” recorded from around the planet the last couple of days, their consequences, and some extreme temperature outlooks, as well as any extreme precipitation reports:

Here is More Climate News from Sunday:

(As usual, this will be a fluid post in which more information gets added during the day as it crosses my radar, crediting all who have put it on-line. Items will be archived on this site for posterity. In most instances click on the pictures of each tweet to see each article. The most noteworthy items will be listed first.)